Evaluate outcomes

Index

Following confirmation that best practices (or the new knowledge) has been implemented, change teams can turn their attention to evaluating outcomes to ascertain the impact of the practice change. Learn more about this important phase of change in this section.

What is this phase?

In the previous phase, you and your change team monitored the adoption of a new practice or intervention that you introduced in a setting. You and your change team can now start to evaluate the outcomes of this intervention or practice change. You can compare outcomes to baseline data collected before to the intervention or practice change to determine the impact and whether the desired goals have been reached.

Evaluating the impact or outcomes of knowledge identifies what differences – if any – resulted after the knowledge was applied. It considers the outcomes from the levels of the person or patient, the health-care provider, the organization, and the broader health system. Evaluation, a complex process, should happen continuously, not merely at a single point in time. A systematic, multidimensional and iterative approach is needed to gather data for the individuals or groups who will be using the knowledge, including persons, health professionals, managers and policymakers (RNAO, 2012).

Data collection post-implementation or post-practice change can vary – you might not wish to do this directly after implementation. Instead, you may want to give time for staff and others to adjust to the change before you evaluate its outcomes.

Evaluation measures – or indicators – are categorized into three main types using the Donabedian framework (1988). The three types of measures described in the table below – structure, process and outcome – are interrelated. For example, by evaluating structure and process measures, change teams can better understand how these measures contribute to outcomes.

Categories of measures

Structure

Definition: The attributes required of the health system, organization, or academic institution to support knowledge use and an evidence-based practice change.

The support or structures that enables the use of knowledge to achieve the change.

Examples:

- updated policies that reflect the clinical guideline’s recommendations

- purchased equipment to support the adherence to the practice change

- established staffing models (for example, roles, levels) to support the practice change

- revised or new documentation forms

- developed clinical pathways that align with best practice

- educated staff on the use of a new assessment tool

Process

Definition: The health-care activities provided to, for and with the persons or populations.

Focuses on person/patient care delivery processes to support process improvement.

Examples:

- provided health teaching or education to persons/families and/or families

- integrated screening tools to assess a health risk (e.g., falls risk)

Outcome

Definition: The effect or impact of the knowledge or practice change on the health status of the persons or populations. Focuses on improving health status outcomes for the person/patient.

Examples:

- change in health status (e.g., the percentage of persons who reported decreased pain according to a validated pain assessment tool)

- staff satisfaction with implementing the practice change

To provide clinical context, we share some examples of indicators per the Donabedian model categories using the Person- and Family-Centred Care (PFCC) Best Practice Guideline (BPG) below.

Structure indicators

Process indicators

Outcome indicators

Using indicators to evaluate BPG implementation

For another example of BPG implementation using Donabedian indicators, watch this 2018 Best Practice Champions Network® presentation on the implementation of RNAO's BPG Assessment and Management of Pressure Injuries for the Interprofessional Team.

Why is this phase important?

The goal of this phase of the KTA action cycle is to determine the impact of the intervention or practice change, how well the change was adopted in the setting and the impact of the intervention or practice change on outcomes (RNAO, 2012; Proctor, 2020; Strauss et al., 2013).

Evaluation can be divided into two main types of outcomes; intervention outcomes and implementation outcomes. Choosing which type/s of outcome to evaluate will depend on the change you are leading and/or the problem you are aiming to address.

Intervention outcomes and their importance in evaluation

Intervention outcomes refer to the success or effectiveness of the intervention. Improvements in clinical and service outcomes are the ultimate goals of care when implementing a practice change or intervention. Typically, data are collected before and after implementation to assess any changes in outcomes, as well as the sustainability of outcomes of the implementation.

Evaluating intervention outcomes provides information about whether the intervention – the specific strategies or activities used to support knowledge use – or practice change worked in your setting.

The typical goals of implementing a practice change are to improve service delivery, the care provided and/or the quality of life of persons/patients. Evaluating intervention outcomes may give you information on the effects of the practice change on individuals and/or groups such as persons/patients, families/caregivers, and health professionals ) by assessing the progress made to achieve the knowledge use and practice change (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Evaluating intervention outcomes answers the following questions (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020):

- Did the implementation of the intervention or practice change result in changes in knowledge, attitudes and skills among health professionals?

- Does the intervention or practice work in our environment?

- Did the practice change or intervention improve the care delivered?

- Did the practice change or intervention improve the person’s overall health and well-being?

- Do the benefits of the practice change or intervention justify a continued allocation of resources?

- Did the practice change or intervention have any unintended effects – whether beneficial or adverse – on people or health professionals?

We give examples of measures of the impact of knowledge use at micro, meso and macro levels below.

Micro level - Person/patient or caregiver/family

Impact of using or applying the knowledge on patients/ caregivers/ families

| Examples of measure | Strategy for data collection |

|

|

Micro level - health professionals

Impact of using or applying the knowledge on health professionals

| Examples of measure | Strategy for data collection |

|

|

Meso level - Organization

Impact of using or applying the knowledge on the organization

| Examples of measure | Strategy for data collection |

|

|

Macro level - System/society

Impact of using or applying the knowledge on the health system or society

| Examples of measure | Strategy for data collection |

|

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Strauss et al., 2013.

Implementation outcomes

It is important to measure the implementation outcomes that were taken to achieve the desired practice change or interventions because if a practice change or an intervention is not well-implemented, it will not be effective (Proctor, 2020). Evaluating implementation outcomes can give you information about whether the intervention or practice change was implemented as intended.

Distinguishing implementation effectiveness from intervention effectiveness is critical for success. When a practice or intervention does not get properly used – or doesn’t get used at all – it is important to determine why the change attempt failed. This can be due to two key factors:

1. Intervention failure: The intervention itself was ineffective. Examples:

- The content of an education series was not deep enough or broad enough to support developing the knowledge needed to achieve the practice change.

- The sessions included only minimal time for hands-on practice to develop the skills to achieve the practice change.

2. Implementation failure: The intervention was potentially effective but was not deployed adequately. Examples:

- The education series effectively addressed the competencies needed to achieve the practice change, but the sessions were poorly attended because they were scheduled during vacation season.

- The education sessions were effective but the staff did not accept the intervention, or didn’t feel it applied to their setting.

And, when an implementation intervention successfully supports knowledge use and a practice change, it can be helpful to evaluate the strategies that were used and how they were used effectively. For example: What steps were taken to support the practice change? How were these steps deployed?

Evaluating implementation outcomes answers the following questions:

- Why does or doesn’t the practice change or intervention work in my setting?

- Did we implement what we intended?

- What worked? What didn't?

Implementation outcomes serve three functions (Khadjesari et al., 2017). They:

- indicate implementation success (e.g., a practice change has been achieved)

- serve as indicators of implementation processes

- serve as important intermediate outcomes for service and clinical outcomes

Identifying and measuring implementation outcomes will allow change teams to understand the implementation processes. You can use it to determine the following regarding an implementation intervention:

- whether it occurred

- whether it was used to support the practice change

- whether it provided the intended benefits to people/patients

Remember: It is difficult to measure the effectiveness of an intervention if your implementation didn’t go as planned! In these cases, understanding the implementation outcomes may assist in explaining why things did or did not work.

It’s important to note that implementation outcomes can be interrelated – they occur in a logical but not necessarily linear sequence. Outcomes earlier in the sequence can contribute to the implementation strategies that will be used later (Glasgow et al., 2019).

There are eight key implementation outcomes that serve as effective indicators of the success of an implementation intervention (Proctor et al., 2011). Outlined below, these eight key outcomes describe how specific variables can impact outcomes.

Types of implementation outcomes

Acceptability

Related terms: Satisfaction

Description: The extent to which persons/patients perceive a treatment, service, practice, or innovation to be agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory.

Strategies for data collection:

- Surveys

- Semi-structured interviews

Feasibility

Related terms: Actual fit or utility, suitability for everyday use, practicability

Description: The extent to which the practice change can be successfully used or carried out within a given setting.

Strategies for data collection:

- Surveys

- Chart audits

Appropriateness

Related terms: Perceived fit, relevance, compatibility, suitability, usefulness, practicability

Description: The extent to which the practice change can be successfully used or carried out within a given setting.

Strategies for data collection:

- Surveys

- Chart audits

Cost

Related terms: Marginal cost, cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit

Description: The financial impact of the practice change. May include costs of treatment delivery, cost of the implementation strategy (for example, an education session or new equipment), cost to the person/patient, and cost of using the service setting.

Strategies for data collection: Administration data

Adoption

Related terms: Uptake, utilization

Description: The intention, initial decision, or action to try or employ the practice change. Adoption may also be called “uptake.”

Strategies for data collection:

- Surveys

- Interviews – Semi-Structured

Fidelity

Related terms: Delivered as intended, adherence, integrity, quality of program delivery

Description: The degree to which an implementation strategy was delivered as prescribed in the original protocol or as intended by program developers. May include multiple dimensions such as content, process, exposure, and dosage.

Strategies for data collection:

- Observation

- Checklists

- Self-reports

Reach

Related terms: Level of institutionalization, spread, service access

Description: The extent to which the practice change is integrated within a setting.

Strategies for data collection:

- Case audits

- Checklists

Sustainability

Related terms: Maintenance, continuation, durability, incorporation, integration, institutionalization, sustained use, routinization

Description: The extent to which a recently implemented practice change is maintained and/or institutionalized within a setting’s ongoing, stable operations.

Strategies for data collection:

- Checklists

- Questionnaires

- Case audits

- Interviews – Semi-Structured

Case studies

Evaluating the impact of implementing the Person- and Family-Centred Care Best Practice Guideline at Spectrum Health Care

Spectrum Health Care (Spectrum), an RNAO Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®), is a home health organization with more than 200 nursing staff across three locations in the province of Ontario, Canada.

Spectrum chose to implement the 2015 Person- and Family-Centred Care (PFCC) Best Practice Guideline (BPG) to enhance person- and family-centred care and to reduce complaints regarding care. Members of the senior leadership team at Spectrum Health Care led implementation together with Spectrum’s Patient and Family Advisory Council.

To support the practice change, Spectrum used the following implementation interventions:

- Conducting a gap analysis to determine the knowledge/practice gap;

- Holding education sessions for staff on person- and family-centred care best practices;

- Revising their care processes to include review of care plans with the person and/or members of their family

- Surveying staff members on their attitudes about person- and family-centred care via surveys

- Developing staff education on communication strategies to support the assessment of a person’s care needs and care plans.

After implementing these interventions, Spectrum assessed the number of complaints received from persons receiving care per 1,000 care visits and compared that to their baseline.

They found a decrease of 42 per cent of complaints from persons received over an 18-month time period at one of the sites that was implementing the PFCC BPG at Spectrum Health Care.

At another site, an 80 per cent reduction in complaints was found following the staff education intervention.

Data analyses overall indicated that the implementation of the PFCC BPG was highly successful in reducing persons' complaints regarding care.

Read more about Spectrum Health care’s results of implementing the PFCC BPG here: Slide 2 (rnao.ca)

Applying the Knowledge-to-Action Framework to reduce wound infections at Perley Health

Perley Health is a designate Long-Term Care Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) which demonstrates a strong commitment to providing evidence-based care. During the pandemic, the team identified skin and wound infection as a clinical concern among their residents. Consistent with the literature, residents at Perley Health experiencing comorbid medical conditions such as frailty, diabetes, and arterial and venous insufficiency were at increased risk for chronic wound infections [1]. Chronic wounds are a prime environment for bacteria, including biofilm, making wound infection a common problem [2] [3]. Managing biofilm, which can affect wound healing by creating chronic inflammation or infection [3], becomes crucial as up to 80 per cent of infections are caused by this type of bacteria [4] [5].

To adopt and integrate best practices, the team at Perley Health decided to implement the Assessment and Management of Pressure Injuries for the Interprofessional Team best practice guideline (BPG). To support a systematic approach to change, four of the action cycle phases of the Knowledge-to-Action Framework, from the Leading Change Toolkit [6] are highlighted below.

Identify the problem

Perley Health’s wound care protocol was audited and the following gaps were identified based on current evidence:

- Aseptic wound cleansing technic could be improved, as nonsterile gauze was used for wound cleansing.

- Wound cleaning solution was not effective to manage microbial load in chronic wounds

- Baseline wound infection data were collected on the number of infected wounds within the organization each month over three years and is ongoing

Adapt to local context

The project was supported by key formal and informal leaders within the organization including the Nurse Specialized in Wounds, Ostomy and continence (NSWOC), the Director of Clinical Practice, a team of wound care champions, the IPAC team and material management. Staff was motivated to improve resident outcomes by lowering infection rates which facilitated the project but many continued to use old supplies so as to not waste material. Providing the rationale for the change and associated best practices improved knowledge uptake, as did removing old supplies to cut down on confusion. Barriers the team encountered included staff turnover and educating new team members.

Select, tailor, implement interventions

The interventions listed below were selected, tailored and implemented based on the evidence that was adapted to the local context. They were purposely chosen to support the clinical teams’ needs on busy units and to creatively overcome staffing challenges. Interventions included:

- use of a wound cleanser containing an antimicrobial

- use of sterile equipment for wound care, including sterile gauze

- creation of a wound-cleansing protocol was created to reflect best practice

- updating and approval of a policy by the Risk Assessment and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers team in collaboration with the director of clinical practice

Perley Health also created and delivered education in two formats designed to be accessible to front-line staff:

- Just-in-Time education was provided on every unit, on every shift, to registered staff by the NSWOC on all shift sets, over a one-month period. Wound care champions were available on each shift to aid in learning and answer additional questions to support the team’s needs.

- A continuing education online learning module was created and uploaded onto Perley Health’s Surge learning platform. Training is included in new hire onboarding and mandatory for yearly education.

Image

An RPN demonstrating how to cleanse a wound using wound cleanser at Perley Health

Evaluate outcomes

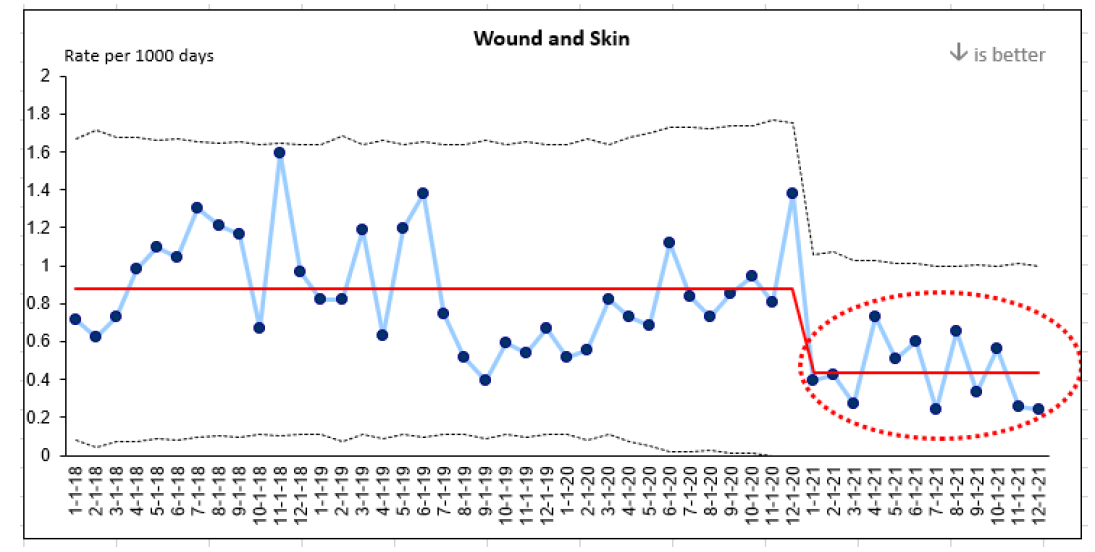

Evaluation indicators were selected to determine the impact of the implementation interventions when compared to baseline data, including the rate of wound and skin infections per 1,000 days. A 50 per cent reduction in wound infections was identified following the implementation of the identified change strategies and education above.

This graph represents four years of data collection on wound infections at Perley Health. Three years of baseline data and one year of post-implementation data are highlighted in red.

References

- Azevedo, M., Lisboa, C., & Rodrigues, A. (2020). Chronic wounds and novel therapeutic approaches. British Journal of Community Nursing, 25 (12), S26-s32.

- Landis, S.J. (2008). Chronic Wound Infection and Antimicrobial Use. Advances in Skin & Wound Care, 21 (11), p 531-540.

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (2016). Clinical best practice guidelines: Assessment and management of pressure injuries for the interprofessional team (3rd ed.). Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario: Toronto, ON.

- Jamal, M., Ahmad, W., Andleeb, S., Jalil, F., Imran, M., Nawaz. M., Hussain, T., Ali, M., Rafiq, M., & Kamil, M.A. (2018). Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. J Chin Med Assoc. 81(1): 7-11.

- Murphy, C., Atkin, L., Swanson, T., Tachi, M., Tan, Y.K., De Ceniga, M.V., Weir, D., Wolcott, R., Ĉernohorská, J., Ciprandi, G., Dissemond, J., James, G.A., Hurlow, J., Lázaro MartÍnez, J.L., Mrozikiewicz-Rakowska, B., & Wilson, P. (2020). Defying hard-to-heal wounds with an early antibiofilm intervention strategy: wound hygiene. J Wound Care, (Sup3b):S1-S26.

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (2022). Leading change toolkit: Knowledge-to-action framework. https://rnao.ca/leading-change-toolkit Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario: Toronto, ON.

Leveraging transformational leadership to engage teams and enhance person- and family-centred care at Hamilton Haldimand Brant (HNHB) Behavioural Supports Ontario (BSO)

Behavioural Supports Ontario (BSO) is a pre-designate Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) serving long-term care (LTC) homes in Hamilton, Haldimand-Norfolk, Brantford, Burlington and Niagara Regions. BSO aims to enhance care and services for older adults with dementia, complex neurological conditions and mental health challenges who present with responsive behaviours through comprehensive assessment and the development of strategies to optimize care for the resident.

The Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant (HNHB) BSO team supports 86 LTC homes with more than 11,200 beds combined. Using transformational leadership and applying key characteristics from the Social Movement Action (SMA) Framework, the organization successfully shifted the culture of the organization to one that supports and sustains high quality and best practices by engaging and motivating staff. Integral to the process was a strong core leadership team of interprofessional staff, intrinsic motivation and momentum.

The organization used RNAO’s BPSO model and gap (opportunity) analysis tools to identify and evaluate areas of improvement in process and practice in three fields of work during the implementation of three RNAO best practice guidelines (BPG) – Person and Family Centered Care, Identification and Assessment of Pain and the Management of Delirium, Dementia and Depression. The impact on personalized care and satisfaction with care are described in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Percentage of residents and families participating in developing their personalized plan of care (assessments completed during referrals)

Evaluation impact: There was a 50.3 per cent increase in residents’ and families’ participation in developing personalized care plans. Data remained consistently above the HNHB average since January 2021.

Figure 2: Number of residents and families satisfied with their involvement in care and treatment planning

Evaluation impact: There was an 80 per cent increase in residents’ and families’ satisfaction with their involvement in the care and treatment plan at the five implementation sites. Survey results from the five implementation sites demonstrated that residents and families responded “always” and “usually” when asked if they were satisfied with their involvement in the care and treatment planning.

In addition to these outcomes, HNHB BSO has identified the following improvements via quantitative data:

- increased number of screenings and assessments for pain completed

- improved consistency in the screening and assessments of delirium, dementia and depression for all clients

- improvement of more than 80 per cent in the number of residents and families satisfied with their involvement in care and treatment planning

Lessons learned

While implementing the BPGs, HNHB BSO discovered several effective strategies, including the following:

- Engaging staff to agree on a common resident-centered goal by developing a “BSO High Five” program. This program recognizes front-line workers who have demonstrated a person-and family-centered approach to care and have motivated other staff to implement and sustain best practices.

- Applying transformational leadership that focused on staff and stakeholder involvement and engaging them throughout the assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation phases of BPG implementation.

- Developing a best practice steering committee that includes formal and informal leaders, staff, and stakeholders. Persons with lived experience are also engaged in the committee to ensure the incorporation of a global perspective into the planning process from the start.

- Ensuring best practices are on all meeting agendas to sustain momentum toward BPG implementation.

- Conducting process and education gap analyses to address areas of improvement as part of a quality improvement project.

- Valuing staff-driven changes and improving synchronization between the project managers and the team to ensure cohesion, a common identity and a shared vision.

- Understanding the importance of going slow and growing the changes to ensure the alignment amongst all staff. This was crucial to the planning and evaluation phases and allowed for the realignment of strategies and approaches, if necessary, during the implementation of projects.

Shared with permission from Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant (HNHB) Behavioural Supports Ontario (BSO)

Practice tips

- Prioritize evaluation and the resources needed to conduct evaluations.

- Strive to maintain timelines for conducting evaluations and analyzing results as timely feedback can help to support the practice change.

- Use existing data systems such as clinical and administrative databases where possible.

- Consider conducting multiple evaluations for long-term change initiatives (each separated with a specified time apart).

- Select the most appropriate indicators that you will use when conducting your evaluations.

- When evaluating practice changes, consider all three indicator types from the Donabedian framework.

- Commit to collecting and analyzing data from the perspectives of all involved including persons/patients, health professionals, and the health system.

- Remember to include planning for evaluation as part of your implementation strategy. This will help make sure you have allocated adequate resources.

Check your progress

- You have identified the outcomes that will be measured to evaluate your change initiative.

- You have determined the number and type of indicators that can be feasibly used to evaluate outcomes.

- You have dedicated personnel or members of the change team to conduct these evaluations.

- You routinely collect and analyze the data and regularly sharing the results with staff. Discussions of the data are used as opportunities to update on areas such as the outcomes of the practice change – outcome indicators – and/or the impact of the interventions used to support the practice change – process indicators.

- You start using evaluation outcomes to drive organizational improvements.

Linking this phase to other framework components

-

Image

Linking this phase to elements of the Social Movement Action Framework

You and your change team’s capacity in the “Evaluate outcomes” phase may be enhanced or accelerated by adding in some elements from the Social Movement Action (SMA) Framework. The KTA and SMA Frameworks are complementary and can be used together to accelerate change uptake and sustainability. In addition to the linking example described earlier in this section, there can be many other points of connection between the two frameworks. Below are two examples for you to consider:

- Public visibility: When evaluating outcomes, you and your change team may include an assessment of the level of stakeholder engagement as an outcome measure. When public domains such as social media platforms have been used to highlight practice changes, you can analyze the number of reposts and views to show uptake. Similarly, if a hashtag has been used for the change initiative, the number of followers and the threaded discussion can also be used to gauge the level of engagement.

- Goals are fully or partially met: Through your evaluation, you and your change team can address whether the goals or vision of the practice change has been met and to what extent. Social movements can result in health transformation being realized through evidence uptake and sustainability.

For more discussion about the dynamic links between the elements of the SMA Framework to the KTA Framework, see the section "Two complementary frameworks".

Getting ready for the next phase: For any practice change, it is never too early to think about how you can ensure that the practice change can be sustained in your setting. Early sustainability planning can help you and your team determine the ways in which the change can be incorporated into work routines or as a standard of care.

In the KTA Framework, the sustainability phase is logically placed after evaluation, because decisions on whether the practice change is compatible and feasible for your setting may change after evaluating the implementation of the practice change. Regardless, thinking about sustainability earlier can help you prepare strategies you can use to sustain the practice change.