Engaging persons with lived experience

- Engaging persons with lived experience

- 1 Considerations for getting started

- 2 Is your change team ready to engage persons with lived experience?

- 3 Engaging advisors and advisory councils

- 4 Examples of effective engagement

- 5 More about engaging persons in change

- 6 Case studies

- 7 Check your progress

- 8 Evaluating engagement

- 9 More resources

Index

- 1. Considerations for getting started

- 2. Is your change team ready to engage persons with lived experience?

- 3. Engaging advisors and advisory councils

- 4. Examples of effective engagement

- 5. More about engaging persons in change

- 6. Case studies

- 7. Check your progress

- 8. Evaluating engagement

- 9. More resources

Engaging persons with lived experience means intentionally partnering with patients, families, or communities throughout the planning, delivery and evaluation of health services to improve quality and safety (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016; Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2017; Nelligan et al., 2002; RNAO, 2015).

This involves engaging persons with lived experience:

- ahead, during and after a practice change to ensure the change is beneficial to the intended end-user (Kearsey, 2021)

- anywhere across the health-care continuum where the practice change is being introduced (for example, service or academic organizations) (RNAO, 2015)

By definition, persons with lived experience include those with first-hand experience of the topic of interest, caregivers and advocates. They provide crucial insight into what matters most for persons impacted by knowledge tools such as guideline recommendations.

Engaging persons with lived experience is important because:

- Engagement improves health outcomes, including increased safety and quality, satisfaction with care, and cost-effective services.

- Engagement helps individualize health care, develops trust, and brings loyalty to an organization by encouraging persons with lived experience to take an active and influential role in decision-making for their own health and wellbeing.

- Engagement enables persons with lived experience to share in collective ownership alongside staff to improve health outcomes.

SOURCES: Carman et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2018; Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2017.

Considerations for getting started

Once you and your change team have confirmed you are committed to including persons with lived experience as part of your change initiative, it may be helpful to focus on the following phases:

- secure commitment from your senior leadership team

- recruit and select persons for the change team

- support the engagement of persons at change team meetings

- show your appreciation to persons for their engagement in the change initiative

Considerations for how to navigate common barriers are also presented for three of the phases.

1. Make sure your senior leadership team commits to engaging persons and their families in your change initiative

- Secure any additional resources you need to successfully onboard persons and family members.

- Determine the level of engagement you desire.

- Confirm that you have the necessary processes, policies and procedures in place to support person and family engagement projects.

How to navigate common barriers to achieve success in this phase:

Lack of senior leadership guidance

- Ensure strong leadership support prior to initiating engagement.

- If possible, engage senior leadership in the planning stages and incorporate their input into the plan.

Leadership changes and staff turnover

- Involve supportive staff who have the leverage to effect change.

- Involve active and engaged leadership staff.

Pressure from senior management to achieve certain objectives that don't align with priorities identified by persons, patients and families

or

Policies and procedures not aligned with participant recommendations

- Where possible, choose recommendations that align with organizational goals and the strategic plan.

- Engage with senior leaders to work on strategies to align person engagement with the organization’s mission, values and strategic directions.

Delays in putting ideas into action that require senior leadership decision-making

Ensure access to leadership to facilitate ideas into action.

SOURCES: Bombard et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2018; Hatlie et al., 2020; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centred Care, 2011; Ocloo et al., 2021; O’Connor et al., 2016 Planetree, 2017; Pougheon-Bertrand et al., 2018; RNAO, 2015; Sharma et al., 2018.

2. Recruit and select persons with lived experience for the change team

- Establish clear eligibility criteria. This may include people who are:

- interested in the topic

- comfortable speaking in a group

- comfortable sharing their personal experiences and able to use them constructively

- able to listen and hear different opinions

- willing to respectfully challenge and question the status quo

- Develop an application process that asks for demographic information, individuals’ connection with the health-care setting, their reasons for wanting to be involved, and their availability in terms of the time commitment.

- Meet with candidates to find out more about their story and determine their fit for the role.

Ensuring success in this phase

Below are common barriers that you and your team may encounter during this phase, and ways you can overcome each barrier to optimize your success:

Disproportionate involvement of providers compared to persons, patients and families

Recruit a higher proportion of persons and families than staff

Biased recruitment

- Aim for a wide representation of persons and families.

- Recruit through several different networks and target within the community of interest.

Failure to recruit those who can effectively communicate and contribute

Select based on certain characteristics and skills.

SOURCES: Bombard et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2018; Hatlie et al., 2020; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centred Care, 2011; Planetree, 2017; Pougheon-Bertrand et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2018; Wieczorek et al., 2018.

3. Support the engagement of persons with lived experience at change team meetings

Develop an orientation program. This could include a meeting prior to the change team meeting, which covers:

- information about the topics and scope

- details about the knowledge tools that will be part of the change initiative, such as RNAO best practice guidelines (BPG) or other data

- a discussion on how confidentiality and privacy will be protected

- organizational processes for person engagement

Begin working together to foster safe and respectful meeting spaces by:

- planning to hold meetings at convenient times and locations

- spending time on introducing everyone and their role

- clarifying the purpose of the team and the roles and responsibilities of each member to validate everyone’s involvement

- emphasizing the anticipated benefits of including persons

- providing an agenda and minutes in advance, with sufficient time for review

Continue working together to recognize and support the unique needs of persons by:

- including in meetings brief stories that capture persons’ experiences and perceptions of care

- monitoring for and limiting the use of medical jargon, and explaining technical terms when used

- asking persons and families direct questions regarding their opinions to encourage them to participate

- acknowledging tensions and differing opinions that may arise, and explaining there are no right or wrong answers – all opinions are respected

- monitoring and discussing the process of working together with ongoing feedback - for example, you could include a debrief session after each meeting

Navigating common barriers to create success in this phase:

Role disagreement between persons, families and staff

Clearly define and formalize the roles and responsibilities for each individual member of the team.

Role disagreement between persons, families and staff

Clearly define and formalize the roles and responsibilities for each individual member of the team.

Limited opportunities outside of meetings to interact and build trust

- Provide opportunities for regular interaction, both formal and informal.

- Allow the time needed to develop trusting relationships.

Fears of intimidation

- Create and use an onboarding and orientation process.

- Provide persons, families and staff with joint training.

Reduced motivation or commitment (for example, no personal motivation, unable to see progress, too time-intensive)

- Institute a term membership to allow new members to join and contribute new ideas.

- Regularly track progress and keep members informed (for example, provide regular project reports, use tracking tools).

- Recognize persons and families may not be able to attend every meeting.

- Reinforce the value of persons and families to the change team by acknowledging their absence and keeping them informed with meeting minutes.

- Offer flexibility in the way persons and families can participate in decisions (for example, in-person meetings, conference calls, and review of written materials).

SOURCES: Bombard et al., 2018; Chegini et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2018; Hatlie et al., 2020; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centred Care, 2011; Ocloo et al., 2021; Planetree, 2017; Sharma et al., 2018; Wieczorek et al., 2018.

Remember:

- Include more than one person with lived experience (aim for at least one-third representation on the committee).

- Recognize that these persons will grow and develop in their role.

- Recognize that these persons may require varying levels of support based on previous experiences.

4. Show your appreciation for persons with lived experience who engaged in the change initiative

- Consider compensating persons and families for their time.

- Offer, where possible, an honorarium to cover the costs incurred as a result of involvement, such as travel, accommodation, parking and meals.

- Respect individuals, first-hand lived experience and recognize how this knowledge can contribute to improved health outcomes.

SOURCES: American Institute for Research, 2019; Boaz et al., 2016; Health Quality Ontario, 2020; Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care, 2011; Kemper et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2018; Planetree, 2017; Sharpe et al., 2018; Wieczorek et al., 2018.

Remember: Once you receive feedback from persons with lived experience, make sure you share aggregated feedback with others who are involved in the change without disclosing identities. This will increase awareness of the importance of the voice of persons throughout the leading change process. This is especially important when the change directly impacts their health and wellbeing.

Is your change team ready to engage persons with lived experience?

- The level of readiness of a change team to accept and embrace persons with lived experience as part of a change initiative can impact outcomes.

- Sometimes, you and your change team members may need to shift your perspectives about persons of lived experience from recipients of care to collaborators or partners in your change initiatives.

- Change teams that decide they are not ready to engage persons as part of the change initiative are encouraged to explore their attitudes and beliefs regarding the role and benefits of persons and families.

- Consider reaching out to other change teams that have successfully engaged persons with lived experience – or to a patient/family advisory council – for guidance and recommendations.

Best practices on engaging persons with lived experience

Here are several best practices from RNAO’s Person- and Family-Centred Care BPG (RNAO, 2015) that you and your team can apply when engaging persons with lived experience:

Communication strategies

During initial meetings, you and your team may wish to focus on getting to know the persons with lived experience, and building a rapport. Here are some communication strategies to help you set the stage for a strong

Preparing for the initial meetings

During initial meetings, you and your team may wish to focus on getting to know the persons with lived experience, and building a rapport. Here are some communication strategies to help you set the stage for a strong working relationship:

When working together

Here are several communication strategies that you and your team can use when interacting with persons with lived experience:

Building active partnerships and meaningful roles

It is important for you and your team to seek the person’s story about their experience, involve them as active partners in meaningful roles, and invite them to serve on committees within the organization.

Valuing diversity

Engagement is always stronger when there is respect and awareness of the diversity of voices. Relationships are strengthened through an intentional process to understand and reflect upon who we are, our unique perspectives, our biases and our assumptions that influence how we behave, and how we relate to others.

The Valuing All Voices Framework

The Valuing All Voices Framework, developed by the University of Manitoba Centre for Healthcare Innovation (2020), embraces a health equity lens to engagement, considering trauma-informed care, intersectionality and reflexivity. The key pillars are:

Download the worksheet "Assessing readiness to engage persons with lived experience in a change initiative".

Engaging advisors and advisory councils

If your organization has already engaged actively with persons with lived experience, you may already have access to community advisors or advisory councils. These individuals and groups have often already been recognized for the work they do in engaging people, and likely have established approaches. Collaborating with them can provide a wealth of knowledge and can help you include the voices of persons with lived experience and their families.

Below are three main types of advisors and advisory councils.

Patient/family advisory council

A group of persons, family members and caregivers who regularly meet with staff and organizational leaders involved in improving the quality, safety and experience of care.

Community health advisors

Laypersons in paid or volunteer positions, trained to support the implementation of community-based initiatives.

Citizen advisory panel

An effective method for community engagement, by which community perspectives are considered in the process of making health service decisions. These individuals may be members of the public, persons/patients, or families and caregivers of persons/patients.

SOURCES: Bombard et al., 2018; Grinspun and Bajnok, 2018; Hatlie et al., 2020; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centred Care, 2011; Liang et al., 2018; Planetree, 2017; Pougheon-Bertrand et al., 2018; RNAO, 2015; Sharma et al., 2018; Timmings et al., 2018; Wieczorek et al., 2018.

Examples of effective engagement

Below are two recorded presentations from change agents on examples of successful engagement of persons with lived experience in implementing RNAO BPGs. Both of the presentations are part of RNAO's Best Practice Champions Network® webinar series highlighting excellence in BPG implementation experiences.

Supporting effective engagement through organizational culture

To successfully engage persons, your organization must believe in the value of partnering with clients to design services (Health Quality Ontario, 2017; RNAO, 2015). Ask yourself: Does your organization already have a culture that commits to engaging persons with lived experience?

The following are several indicators to help assess whether your senior leadership is committed to engaging persons with lived experience. You can also use these indicators to help you open and guide a conversation about creating a culture committed to engaging persons.

See considerations for getting started: #1 for strategies to overcome any barriers at the senior leadership level.

Role of senior leaders

Senior leaders are responsible for setting priorities and directions based on the mission and vision for their organization. They typically commit to embedding the engagement of persons with lived experience into their organizational culture by:

- including the attributes of engaging persons with lived experience into the mission, vision, value statements and strategies of the organization

- inspiring and leading through example by modelling to staff their own encounters with persons with lived experience

- making sure resources are available for the ongoing development, education and mentorship of staff in engaging persons with lived experience

- monitoring, collecting and evaluating data on persons’ experiences of health care and services, and using these perspectives to inform organizational improvements

- incorporating expectations for engaging persons with lived experience into the organization’s system designs (policy reviews, development of procedures, hiring practices and performance reviews of staff)

- making sure staff feels respected and valued, recognizing and celebrating when staff partner effectively with persons with lived experience

SOURCE: RNAO, 2015

More about engaging persons in change

Persons with lived experience bring unique and valuable insights to change. They:

- provide personal perspectives through storytelling, surveys, focus groups and targeted groups

- represent the voices, broad views and experiences of a range of people affected by a condition

- give experiential advice to influence decisions

- should be valued for significant knowledge as recipients of care

- may take the form of informant, advocate, advisor, expert, or partner for the experiences and journeys they have lived through

SOURCES: Health Quality Ontario, 2017; RNAO, 2015; Tong et al., 2019.

Continuum of engagement of persons with lived experience

Engaging persons with lived experience ranges from consultation to involvement, to partnership and shared leadership, depending on the desire of all involved (RNAO, 2015). This continuum of engagement can help you plan to engage people and to assess your organization’s current engagement practices.

Before initiating engagement strategies, it may be helpful to first assess whether your organization has been engaging persons with lived experience, and identify organizational practices that support engagement. And – depending on where on the continuum your organization is – an assessment can help to identify priority areas for improving, strengthening or sustaining engagement practices.

Approaches for planning and assessing engagement across the continuum are also summarized below.

Characteristics and approaches for planning and assessing engagement across the continuum

Description

Characteristics

Approaches for planning and assessing engagement

SOURCES : Carman et al., 2013; Kemper et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2018; Planetree, 2017; RNAO, 2015; Wieczorek et al., 2018, Sharma et al., 2016.

Case studies

Engaging Patient Family Advisors to advance guideline implementation at Scarborough Health Network

Scarborough Health Network (SHN) (Home - Scarborough Health Network (shn.ca) is an organization pursuing Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) designation in Scarborough, Ontario, Canada. Patient Family Advisors (PFAs) are a vital part of SHN’s philosophy of care, representing the diverse community SHN serves. A key element of the PFA role is sharing lived experiences with SHN staff and the Scarborough community.

SHN has demonstrated commitment to the role of PFAs within their organization by creating a new department for health equity, patient and community engagement (HEPCE). This department focuses on:

- recruiting, onboarding, managing, recognizing and retaining PFAs

- educating staff on best practices related to engaging with PFAs

During recruitment and onboarding, the HEPCE and current PFAs educate potential PFAs about the role’s scope and expectations. All PFAs are also provided with information on how to share their patient or caregiver story with their audience.

PFAs have played an important role in SHN’s BPSO committee. Indeed, one PFA has been integral to the process of recruiting and engaging champions at SHN throughout the COVID-19 pandemic’s health human resources (HHR) crisis. Their role has included participating in champions’ virtual drop-in sessions (2020-2021) and in-person roadshows (2022).

Champion roadshows are events during, which SHN practice leaders and PFAs promote the BPSO program, share best practice guidelines and recruit champions around the organization, without asking busy staff members to leave their units.

The PFA also supported the recruitment and engagement of champions by:

- collaborating with other champions and working group members to plan champions’ drop-in sessions and roadshows

- working alongside the team to plan safe spaces for staff and PFAs to share their stories

- sharing stories of positive experiences with staff members in relation to the impact of best practices (for example, RNAO’s Person and Family Centred-Care best practice guideline) on their experience

Staff members have reported being motivated to become best practice champions after attending a champion’s roadshow. SHN has also consistently gained champions during the HHR crisis and maintains at least 15 per cent of nursing staff as best practice champions.

The PFA’s role was vital to demonstrating the lasting impact of best practices. They have expressed feeling empowered by their role in BPSO work, expressing that the work helped them find their voice and become part of the movement to promote and implement best practices.

Overall, PFAs play an essential – and dual – role in supporting the implementation of best practices at SHN. In line with person- and family-centred care, PFAs assume an outward-facing role in shaping the implementation of best practices and SHN’s values. In addition, they also act in an inward-facing role to support the bolstering of champions.

To learn more about the PFA role at SHN, please visit the following link: Patient Family Advisors.

Shared with permission by Scarborough Health Network

Integrating patient partners in change – Lessons learned from Kidney Health Australia

In early 2018, Kidney Health Australia (KHA) developed a guideline for managing percutaneous renal biopsies for individuals with chronic kidney disease (Scholes-Robertson et al., 2019). KHA included 40 persons from across Australia with lived experience of chronic kidney disease and their caregivers – “patient partners”. KHA asked patient partners to prioritize which topics were most important to them during a percutaneous renal biopsy.

Patient partners valued: minimizing discomfort and disruption, protecting their kidneys, enabling self-management, and making sure that support for families and caregivers would be available. They indicated that all of this would help alleviate anxiety and avoid undue stress. Their voices were heard, and KHA effectively incorporated these suggestions in guideline development.

Notably, there were marked differences between the priorities identified by the content experts on the guideline development working group, versus what the patient partners perceived to be important to their health and wellbeing, as shown in the table below.

|

Topics prioritized by content experts |

Topics prioritized by patient partners |

|

|

Co-designing change through the active engagement of persons with lived experience - Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital (Holland Bloorview) is a designated Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Canada. Holland Bloorview has an award-winning Family Leadership Program (FLP), through which family leaders partner with the organization and the Bloorview Research Institute to co-design, shape and improve services, programs and policies.

These family leaders are families and caregivers who have received services at Holland Bloorview and have lived experiences of paediatric disability. Their roles include mentoring other families, acting as advisors to committees and working groups, and co-teaching workshops to students and other families.

One example of a successful implementation co-design within Holland Broadview is the ENFit™ Working Group. This interprofessional team works on the adoption of a new type of connection on products used for enteral feeding – or feeding directly through the stomach or intestine via a tube. By introducing the ENFit™ system, a best practice safety standard, the working group plans to reduce the risk of disconnecting the feeding tube from other medical tubes. This in turn decreases harm to children and youth who require enteral feeding.

The working group invited a family member and leader whose son had received services at Holland Bloorview. This family member had significant lived experience with enteral feeding management, enteral medication administration, and other complexities associated with enteral products. During the meetings, the potential impacts on persons and families were emphasized. The working group engaged the family member by:

- co-creating the implementation plan

- involving them in a failure mode and effects analysis highlighting the impact of the feeding tube supplies on transitions to home, school and other care settings

- working with the family member to advocate for safe transitions within the provincial pediatric system, which led to the development of the Ontario Pediatric ENFit™ Group

To learn more about Holland Bloorview’s experience in partnering with families in a co-design process, watch their 38-minute webinar: The Power of Family Partnerships

Shared with permission from Holland Bloorview

Check your progress

- You have carefully considered the benefits and value of including persons and families in your change initiative.

- You have secured support from your senior leaders.

- You have checked all the organizational policies, procedures for recruiting, selecting and involving persons and families.

- You have ongoing approaches to check in with persons and families to offer support.

- You have active attendance and engagement of persons and families in change team meetings.

- You have an orientation plan for persons and families to support onboarding.

- You have used additional resources (for example, ones from this toolkit) to help you carefully plan how to engage persons and families in an effective, inclusive and respectful manner.

- You regularly evaluate how persons and families are experiencing engagement in your change initiative.

Evaluating engagement

You and your team may consider collecting continuous feedback from persons with lived experience to get input on how you can improve their experience during the partnership. Obtaining continuous feedback, and reflecting and taking action on ways to improve, can help you maintain your focus on engaging persons with lived experience (RNAO, 2015).

Note: Before seeking feedback from persons, you and your team must ask if they wish to participate in evaluating their experiences.

Methods to get feedback:

- questionnaires

- interviews

- small group discussions

- observations

Guiding questions to help you think about how to evaluate the engagement experience (Alberta Health Services, 2014):

- How did the contributions of the persons with lived experience impact the project, and have their contributions been communicated to the persons?

- How were the initial expectations of persons being met at the end of the project?

- How collaborative was the process?

Steps for designing an evaluation plan

Evaluating the engagement process and its outcomes is an important component to engaging persons with lived experience and to identifying whether you have met your objectives. The perspectives of the persons and of your team should be equal when designing your evaluation plan.

Here are some steps provided by Alberta Health Services (2014):

- Work with the persons to create an evaluation outline. Design an evaluation timeline early in the engagement initiative that includes routine check-ins (for example, before and after meetings). Routine check-ins allow you to see whether the project is on track for meeting mutually-determined goals and objectives. These check-ins also allow you to make adjustments to the plan as issues arise.

- Determine what needs to be evaluated and how to evaluate it. Decide what questions need to be asked to determine if the objectives of both the engagement process and the project are being met. Determine the best method for evaluation of the data you need – for example, would surveys or interviews be more effective? Make sure that the evaluation questions and process are mutually determined by all those involved and meet their needs.

- Be clear about the data needed to evaluate. Specify the exact data you will need to complete the evaluation, such as time-keeping records, expense reports and meeting notes. This will help those involved in the evaluation make sure to track and record data throughout the project.

- Develop an evaluation plan. Identify key milestones and timelines, as well as who will be involved in the evaluation process and what they will do (for example, who will conduct the interview; report the outcomes of the evaluation to supervisors, etc.)

- Determine what will be done with the evaluation information. Will the results be sent to managers or other stakeholders? If so, clarify which stakeholders, and who will share the information.

Evaluating the engagement process and outcomes

You may wish to evaluate the process of engagement – how the project activities unfolded, the outcomes of the engagement – what was achieved or both.

To evaluate the engagement process, you can look at:

- representation from the population of interest

- early involvement of persons with lived experience

- number and level of clearly defined tasks for persons with lived experience

- transparency of decision-making process

- clear articulation of roles and responsibilities

- satisfaction of persons and team with process

- timeliness, participation rate and costs incurred

SOURCES: Alberta Health Services (2014); Capital Health (2011).

Engagement process questions

Below are sample questions to generate feedback from persons and team members on the engagement process:

For persons with lived experience

- How detailed, complete and easy to understand was the background information provided to you?

- Do you feel you had the right information to take part in the discussion?

- Overall, how is your experience as a partner?

- How could your experience as a partner be improved?

- What would you do differently next time?

- Any additional comments?

For team members

- How many persons with lived experience participated in the engagement activity?

- Were the right persons at the table?

- Did you use any incentives to encourage participation? If so, what incentives did you use?

- Were engagement costs within budget?

SOURCES: Alberta Health Services (2014); Capital Health (2011); McMaster University (2018).

To evaluate the outcomes of engagement, you can look at:

- influence of and contributions from persons with lived experience

- persons’ experience of being heard and understood

- effect on team members’ attitudes towards the engagement experience

- engagement goals

SOURCES: Alberta Health Services (2014); Capital Health (2011).

Engagement outcomes questions

Below are sample questions to generate feedback from persons and team members on the engagement outcomes.

For persons with lived experience

- Overall, how satisfied are you that your opinions were heard and understood?

- Overall, how confident are you that your opinions will influence the final decision or outcome?

- How satisfied are you with the decision or outcome?

- How satisfied are you with the communication of the decision or outcome?

- Any additional comments?

For team members

- Did the patient engagement activity or the participation of the persons with lived experience validate their perspectives?

- Were the decision and rationale communicated to the persons?

- Was input from the persons included in the decision-making process?

- Was the organizational goal and promise back to persons achieved?

- What would you do differently next time?

SOURCES: Alberta Health Services (2014); Capital Health (2011); McMaster University (2018).

More resources

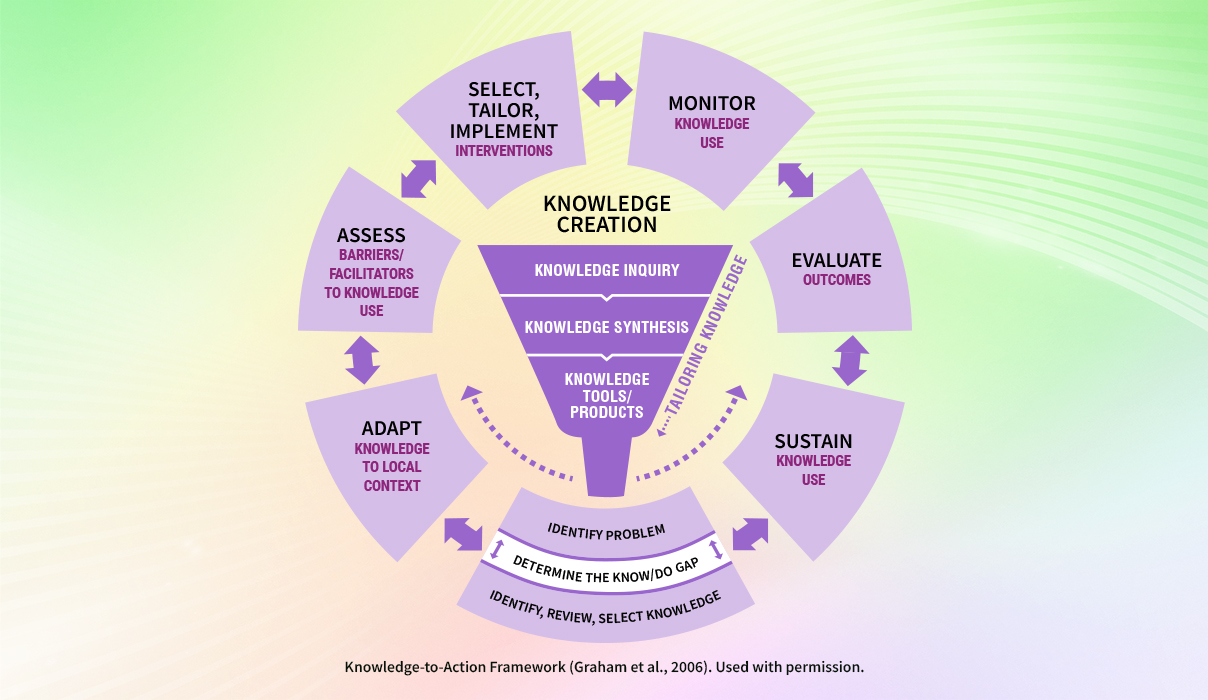

Want to learn more about using the strategies of the SMA and KTA frameworks to support your change? Sign up for the RNAO Best Practice Champions training course.