Case studies

Social Movement Action Framework

Using social media to increase public visibility and raise awareness

Social media is used by RNAO regularly to advocate for advancing the rights of Ontarians, including residents of long-term care homes. Read this case study that includes examples of effective social media campaigns advocating for the Nursing home Basic Care Guarantee.

RNAO uses social media campaigns to increase public visibility and raise awareness of issues. One example: RNAO’s call on the Ontario government to mandate recommendations set out in its Nursing Home Basic Care Guarantee. The campaign incorporated the hashtags #LTC #BasicCareGuarantee and #4Hours4Seniors to raise awareness of the staffing crisis in long-term care (LTC) and to encourage the public, health professionals, the government, LTC residents and their families to mobilize change.

As the campaign evolved, so did the visuals and the messaging. The three examples below show the stages of the campaign as it gained attention and momentum – from “good” through “better” to “best.”

RNAO developed an Action Alert (AA) to mobilize collective action to advocate for nursing home residents. The link to the AA, the graphic, the messaging and the hashtag #4Hours4Seniors were all shared on social media to urge others to sign and share the AA. People were also encouraged to use the hashtag to contribute to the dialogue about the LTC crisis.

The social media campaign aimed to support the goal set out in the AA – encourage as many people as possible to add their signatures to urge action from key political leaders.

This is a good example of a social media campaign, incorporating a graphic, supportive messaging, a call-to-action (the link to the AA) and a specific hashtag.

In this example, RNAO staff members are holding signs identifying why #4Hours4Seniors matters to them. The hashtag is used consistently and individual reasons for supporting the cause are illustrated.

This is a better example of a social media campaign – it brings a personal touch to the campaign and allows supporters to share why they want to join the conversation. It also brought life to the hashtag and to the purpose of the campaign.

Image

In this example, RNAO collaborated with F.J. Davey Home in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada to encourage residents to share their “why” for wanting #4Hours4Seniors. Building on the same idea as the “better” example given above, this example truly brought a face to the reason for the campaign in the first place. RNAO shared the photos and quotes from residents on its social media feeds (Instagram, Facebook and Twitter) alongside the hashtag #4Hours4Seniors.

For example, M. Doan, a senior living at the F.J. Davey Home, shared: “I am a very independent person, but my wife on the other hand isn’t and she means the world to me. With four hours of care, it doesn’t need to be rushed. And who wouldn’t want to see her beautiful smile for four hours!" (https://twitter.com/RNAO/status/1336781022780928000).

The photos are powerful as they show a real-life married couple living in a LTC home – two of the many residents RNAO advocated for through its AA and its ongoing call for a Nursing Home Basic Care Guarantee. The posters held by the couple express their personal values of dignity and comfort.

Valuing the need for hospice and palliative care services

Advocacy for humane death and dying care practices led to the valuing and realization of hospice and palliative care services in South Australia.

Advocacy for humane death and dying care practices led to the valuing and realization of hospice and palliative care services in South Australia in the 1990s (Elsey, 1998). Early hospice and palliative care advocates pressed for comprehensive community services provided by knowledgeable, humane and compassionate care providers who understood and supported the need for an alternative to medical practices in this area.

Advocates also recognized the need for funding, legislation, support of relevant volunteer organizations, and capacity-building in health professionals to ensure effective delivery of hospice and palliative care services.

Rooting the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project in Indigenous values

A diabetes prevention project in a First Nations community in Quebec was effectively implemented through multiple strategies including the integration of Indigenous values and beliefs.

The Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project (ksdpp.org) in the First Nations reserve of the Mohawks of the Kahnawake in Quebec, Canada aims to prevent type 2 diabetes in Kahnawake by empowering community members to care for their health. Project leaders were informed at the outset by evidence that demonstrated a two-fold higher risk of diabetes and diabetes-related complications in adults (Tremblay et al., 2018).

To be meaningful for community members, the change was rooted in the values and traditions of Kanien’kehá:ka beliefs, incorporating a holistic approach of spiritual, emotional, physical and mental dimensions that reflect wellbeing. The project’s focus aligned with the value of protecting and promoting the health of future generations. By linking the change in values, families and other community members were more invested in the cause.

Knowledge-to-Action Framework

Applying the Knowledge-to-Action Framework to reduce wound infections at Perley Health

A case study on reducing wound infections at Perley Health in Ottawa, Ontario to advance best practices using the Knowledge-to-Action framework.

Perley Health is a designate Long-Term Care Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) which demonstrates a strong commitment to providing evidence-based care. During the pandemic, the team identified skin and wound infection as a clinical concern among their residents. Consistent with the literature, residents at Perley Health experiencing comorbid medical conditions such as frailty, diabetes, and arterial and venous insufficiency were at increased risk for chronic wound infections [1]. Chronic wounds are a prime environment for bacteria, including biofilm, making wound infection a common problem [2] [3]. Managing biofilm, which can affect wound healing by creating chronic inflammation or infection [3], becomes crucial as up to 80 per cent of infections are caused by this type of bacteria [4] [5].

To adopt and integrate best practices, the team at Perley Health decided to implement the Assessment and Management of Pressure Injuries for the Interprofessional Team best practice guideline (BPG). To support a systematic approach to change, four of the action cycle phases of the Knowledge-to-Action Framework, from the Leading Change Toolkit [6] are highlighted below.

Identify the problem

Perley Health’s wound care protocol was audited and the following gaps were identified based on current evidence:

- Aseptic wound cleansing technic could be improved, as nonsterile gauze was used for wound cleansing.

- Wound cleaning solution was not effective to manage microbial load in chronic wounds

- Baseline wound infection data were collected on the number of infected wounds within the organization each month over three years and is ongoing

Adapt to local context

The project was supported by key formal and informal leaders within the organization including the Nurse Specialized in Wounds, Ostomy and continence (NSWOC), the Director of Clinical Practice, a team of wound care champions, the IPAC team and material management. Staff was motivated to improve resident outcomes by lowering infection rates which facilitated the project but many continued to use old supplies so as to not waste material. Providing the rationale for the change and associated best practices improved knowledge uptake, as did removing old supplies to cut down on confusion. Barriers the team encountered included staff turnover and educating new team members.

Select, tailor, implement interventions

The interventions listed below were selected, tailored and implemented based on the evidence that was adapted to the local context. They were purposely chosen to support the clinical teams’ needs on busy units and to creatively overcome staffing challenges. Interventions included:

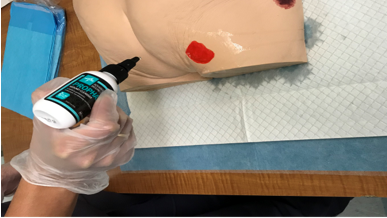

- use of a wound cleanser containing an antimicrobial

- use of sterile equipment for wound care, including sterile gauze

- creation of a wound-cleansing protocol was created to reflect best practice

- updating and approval of a policy by the Risk Assessment and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers team in collaboration with the director of clinical practice

Perley Health also created and delivered education in two formats designed to be accessible to front-line staff:

- Just-in-Time education was provided on every unit, on every shift, to registered staff by the NSWOC on all shift sets, over a one-month period. Wound care champions were available on each shift to aid in learning and answer additional questions to support the team’s needs.

- A continuing education online learning module was created and uploaded onto Perley Health’s Surge learning platform. Training is included in new hire onboarding and mandatory for yearly education.

Image

An RPN demonstrating how to cleanse a wound using wound cleanser at Perley Health

Evaluate outcomes

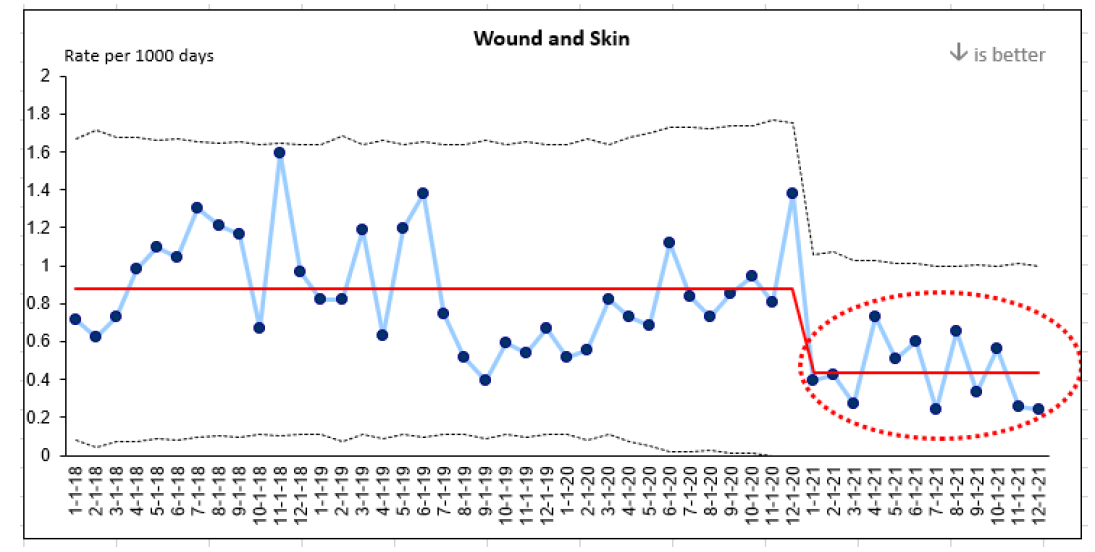

Evaluation indicators were selected to determine the impact of the implementation interventions when compared to baseline data, including the rate of wound and skin infections per 1,000 days. A 50 per cent reduction in wound infections was identified following the implementation of the identified change strategies and education above.

This graph represents four years of data collection on wound infections at Perley Health. Three years of baseline data and one year of post-implementation data are highlighted in red.

References

- Azevedo, M., Lisboa, C., & Rodrigues, A. (2020). Chronic wounds and novel therapeutic approaches. British Journal of Community Nursing, 25 (12), S26-s32.

- Landis, S.J. (2008). Chronic Wound Infection and Antimicrobial Use. Advances in Skin & Wound Care, 21 (11), p 531-540.

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (2016). Clinical best practice guidelines: Assessment and management of pressure injuries for the interprofessional team (3rd ed.). Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario: Toronto, ON.

- Jamal, M., Ahmad, W., Andleeb, S., Jalil, F., Imran, M., Nawaz. M., Hussain, T., Ali, M., Rafiq, M., & Kamil, M.A. (2018). Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. J Chin Med Assoc. 81(1): 7-11.

- Murphy, C., Atkin, L., Swanson, T., Tachi, M., Tan, Y.K., De Ceniga, M.V., Weir, D., Wolcott, R., Ĉernohorská, J., Ciprandi, G., Dissemond, J., James, G.A., Hurlow, J., Lázaro MartÍnez, J.L., Mrozikiewicz-Rakowska, B., & Wilson, P. (2020). Defying hard-to-heal wounds with an early antibiofilm intervention strategy: wound hygiene. J Wound Care, (Sup3b):S1-S26.

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (2022). Leading change toolkit: Knowledge-to-action framework. https://rnao.ca/leading-change-toolkit Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario: Toronto, ON.

Overcoming barriers to evidence-based practice – Lessons learned from DongZhiMen Hospital and Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (BUCM) School of Nursing

DongZhiMen Hospital and Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (BUCM) School of Nursing are international BPSOs in Beijing, China. Staff at the sites identified barriers to the use of evidence in practice including heavy workloads, cultural differences and reluctant attitudes about using evidence to inform practice.

DongZhiMen Hospital and Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (BUCM) School of Nursing are international BPSOs in Beijing, China. They identified barriers to the use of evidence in practice including heavy workloads, cultural differences and reluctant attitudes about using evidence to inform practice. The assessment and identification of barriers allowed change teams to develop effective strategies for implementation with the input of stakeholders.

For example, for the implementation of the RNAO best practice guideline Assessment and management of foot ulcers for people with diabetes, barriers included

- nursing shortages across China,

- a lack of training to support the development of knowledge and skills in evidence-based nursing practice,

- the costs of guideline implementation. and

- practice recommendations that exceeded local nursing scope.

SOURCE: Transforming Nursing Through Knowledge, 2018.

Facilitating an evidence-based culture at Unity Health Toronto - St. Michael’s Hospital

Unity Health Toronto - St. Michael’s Hospital, a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) has embedded evidence-based practices into its culture and daily work processes as part of its corporate strategy.

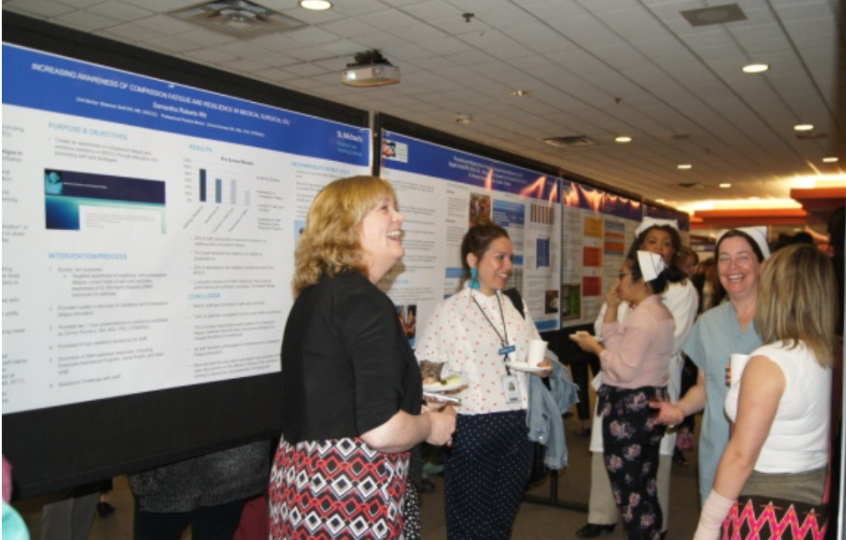

Unity Health Toronto - St. Michael’s Hospital, a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Canada, has embedded evidence-based practices into its culture and daily work processes. Evidence-based practice is part of the hospital’s corporate strategy. It has invested resources to build a critical mass (over 30 per cent) of staff members who are best practice champions.

The hospital also provides multiple capacity-building opportunities, including a community of practice, boot camps, booster sessions and mentorship. The annual Nursing Week Gallery Walk, depicted in the image above, is just one way that St. Michael’s Hospital profiles the work of champions and others dedicated to using evidence to inform change initiatives.

SOURCE: Transforming Nursing Through Knowledge, 2018.

Engaging Persons with Lived Experiences

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital: Co-designing change through the active engagement of persons with lived experience

A case study from Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital focused on engaging persons with lived experience in a change process.

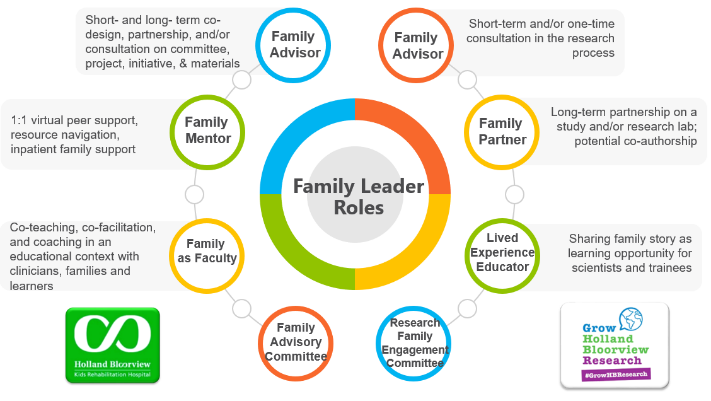

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital (hereafter referred to as Holland Bloorview) is a designated Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Holland Bloorview has an award-winning Family Leadership Program (FLP), through which family leaders partner with the organization and the Bloorview Research Institute to co-design, shape, and improve services, programs, and policies. Family leaders are families and caregivers who have received services at Holland Bloorview, and have lived experiences of paediatric disability. Family leaders’ roles include being a mentor to other families, an advisor to committees and working groups, and faculty who co-teach workshops to students and other families.

Family Leader Roles at Holland Bloorview. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

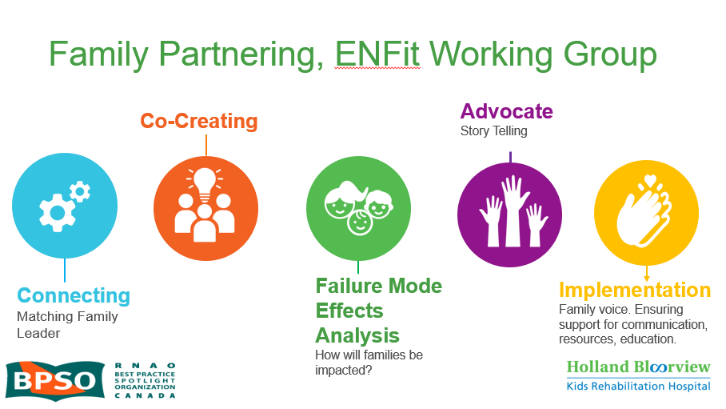

The ENFit™ Working Group is an example of a successful implementation co-design process within Holland Bloorview. The ENFit™ Working Group is an interprofessional team working on the adoption of a new type of connection on products used for enteral feeding [feeding directly through the stomach or intestine via a tube]. By introducing the ENFit™ system, a best practice safety standard, the working group plans to reduce the risk of disconnecting the feeding tube from other medical tubes, and thus decrease harm to children and youth who require enteral feeding.

Family Partnering with the EnFit Working Group. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

The working group invited a family member and leader whose son had received services at Holland Bloorview. This family member had significant lived experience with enteral feeding management, enteral medication administration, and other complexities associated with enteral products. During the meetings, great attention was given to the potential impacts on persons and families. The group engaged the family member by:

- co-creating the implementation plan

- involving them in a failure mode affects analysis, which highlighted the impact of the feeding tube supplies on transitions to home, school, and other care settings

- working with the family member to advocate for safe transitions within the provincial pediatric system, which led to the development of the Ontario Pediatric ENFit™ Group

To learn more about Holland Bloorview’s experience in partnering with families in a co-design process, watch their 38-minute webinar: The Power of Family Partnerships.