Case studies

Social Movement Action Framework

Advancing knowledge uptake and sustainability through RNAO's Best Practice Champions Network®

The Best Practice Champions Network® has been engaging change agents for over two decades to facilitate connection, a sense of belonging and a place to continue the implementation of best practice guidelines.

Launched in 2002, the RNAO Best Practice Champions Network® supports the active engagement of volunteer peer Best Practice Champions in knowledge exchange amongst one another, and between them and RNAO. Through this international network, more than 100,000 champions access tools and strategies such as workshops, webinars and online modules (Grinspun, 2018).

Maintaining momentum to achieve excellence - Unity Health Toronto: St. Michael's Hospital

To keep the momentum as a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®), Unity Health Toronto: St. Michael’s Hospital engaged their Professional Practice team as change leaders. Read more in this case study.

To keep the momentum as a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) implementing, evaluating and sustaining RNAO best practice guidelines (BPGs), Unity Health Toronto: St. Michael’s Hospital, https://rnao.ca/bpg/bpso/st-michaels-hospital, an acute care facility in Toronto, Ontario, Canada engaged their Professional Practice team as change leaders. Strategies the Professional Practice team have used to maintain momentum include:

- profiling the activities, leadership and achievements of their champions and other change agents

- using newsletters, posters and pins to promote BPSO and increase its visibility

- participating in poster galleries and nursing rounds

- publishing multiple articles in scholarly and professional journals to highlight key accomplishments and deliverables

- creating and using an intranet site to update staff on BPSO activities (Ferris, Jeffs, Krock, & Skiffington, 2018).

Sustaining a health system change with momentum

To create system level changes in health-care in the United Kingdom, momentum was fostered to achieve goals. Read more in this case study.

The Health as a Social Movement project for the National Health Services (NHS) developed the Programme Theory of Change to create system-level changes in health care in the United Kingdom.

The project used this theoretical model to provide impetus for change by defining goals for the change. These goals included connecting individuals, groups and organizations acting as change agents with the health system to mobilize local action for health.

Momentum played a pivotal role in achieving system change and transformation. Indicators of momentum included:

- an increase in social connectedness of individuals, groups and/or organizations

- higher levels of control, resourcefulness and resilience in the community

- an increase in change agents’ confidence and influence over the health system

The sustained momentum arising from the individual and collective action aimed to support a preventable and sustainable health system, characterized as having:

- improvements in local services

- an integration of determinants of health into service provision

- higher levels of health and well-being (Arnold et al., 2018).

Knowledge-to-Action Framework

Conducting gap analyses to successfully implement new clinical practices at Tilbury Manor

Tilbury Manor, a long-term care home, chose to focus on provincially-mandated “required programs” when seeking to improve resident care using a gap analysis.

Tilbury Manor, a 75-resident long-term care home in Tilbury chose to focus on provincially-mandated “required programs” (fall prevention, skin and wound care, continence care, bowel management and pain management) when seeking to improve resident care.

They conducted a gap analysis to compare their current practices with the best practices outlined in related RNAO best practice guidelines. Their analysis included an assessment of clinical practices, policies and documentation systems. The results of the gap analysis helped them create specific action plans.

Tilbury Manor then formed project teams led by nurses and supported by a team of champions. These teams proceeded to educate staff, implement new clinical practices, conduct care reviews and conduct audits.

Multiple positive outcomes were reported as a result of implementing these best practices including reductions in reports of pain, less use of restraints, and less falls, pressure ulcers and urinary tract infections.

Evaluating the impact of implementing the Person- and Family-Centred Care Best Practice Guideline at Spectrum Health Care

Spectrum Health Care, a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) and home health organization, evaluated care outcomes after implementing the Person- and Family-Centred best practice guideline (BPG).

Spectrum Health Care (Spectrum), an RNAO Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®), is a home health organization with more than 200 nursing staff across three locations in the province of Ontario, Canada.

Spectrum chose to implement the 2015 Person- and Family-Centred Care (PFCC) Best Practice Guideline (BPG) to enhance person- and family-centred care and to reduce complaints regarding care. Members of the senior leadership team at Spectrum Health Care led implementation together with Spectrum’s Patient and Family Advisory Council.

To support the practice change, Spectrum used the following implementation interventions:

- Conducting a gap analysis to determine the knowledge/practice gap;

- Holding education sessions for staff on person- and family-centred care best practices;

- Revising their care processes to include review of care plans with the person and/or members of their family

- Surveying staff members on their attitudes about person- and family-centred care via surveys

- Developing staff education on communication strategies to support the assessment of a person’s care needs and care plans.

After implementing these interventions, Spectrum assessed the number of complaints received from persons receiving care per 1,000 care visits and compared that to their baseline.

They found a decrease of 42 per cent of complaints from persons received over an 18-month time period at one of the sites that was implementing the PFCC BPG at Spectrum Health Care.

At another site, an 80 per cent reduction in complaints was found following the staff education intervention.

Data analyses overall indicated that the implementation of the PFCC BPG was highly successful in reducing persons' complaints regarding care.

Read more about Spectrum Health care’s results of implementing the PFCC BPG here: Slide 2 (rnao.ca)

Leveraging innovative quality monitoring - Humber River Hospital

Humber River Hospital is an acute care facility that has used continuous monitoring to determine the impact of BPG implementation and staff performance.

A major acute-care hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Humber River Hospital (now Humber River Health) has used continuous monitoring to determine the impact of their BPG implementation and staff performance.

These tiles, displayed on large screen monitors in a Command Centre (pictured above), are integrated into the daily delivery of care to support physicians, nurses, and other clinical staff. Each row within the tile represents a patient, followed by where they are located. By clicking on a patient, staff can see more information regarding the clinical criteria that put them on the tile.

With every patient, there is an expected time in which the issue should be resolved based on a service level set by the hospital. If the system detects that the process is taking longer than expected, the icon will escalate to amber and then to red, indicating a higher level of alert.

Tiles also include several quality monitoring indicators based on RNAO's best practice guidelines (BPG) related to fall risk intervention, wound and skin management, pain management and delirium management. By centralizing data in the Command Centre, the monitoring indicators empower clinicians so that they can intervene in a timely manner to ensure that best practices are followed.

Read more about this innovative quality monitoring approach here: https://www.hrh.ca/2020/08/04/cc-risk-of-harm/

Engaging Persons with Lived Experiences

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital: Co-designing change through the active engagement of persons with lived experience

A case study from Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital focused on engaging persons with lived experience in a change process.

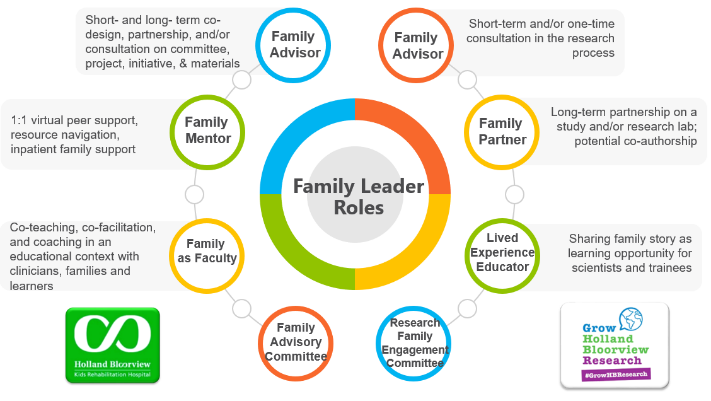

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital (hereafter referred to as Holland Bloorview) is a designated Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Holland Bloorview has an award-winning Family Leadership Program (FLP), through which family leaders partner with the organization and the Bloorview Research Institute to co-design, shape, and improve services, programs, and policies. Family leaders are families and caregivers who have received services at Holland Bloorview, and have lived experiences of paediatric disability. Family leaders’ roles include being a mentor to other families, an advisor to committees and working groups, and faculty who co-teach workshops to students and other families.

Family Leader Roles at Holland Bloorview. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

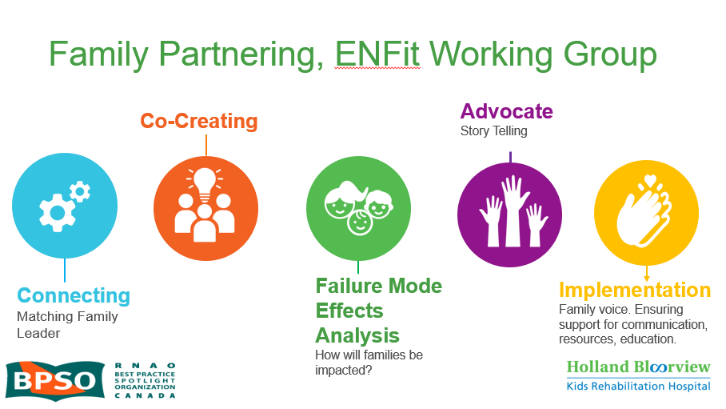

The ENFit™ Working Group is an example of a successful implementation co-design process within Holland Bloorview. The ENFit™ Working Group is an interprofessional team working on the adoption of a new type of connection on products used for enteral feeding [feeding directly through the stomach or intestine via a tube]. By introducing the ENFit™ system, a best practice safety standard, the working group plans to reduce the risk of disconnecting the feeding tube from other medical tubes, and thus decrease harm to children and youth who require enteral feeding.

Family Partnering with the EnFit Working Group. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

The working group invited a family member and leader whose son had received services at Holland Bloorview. This family member had significant lived experience with enteral feeding management, enteral medication administration, and other complexities associated with enteral products. During the meetings, great attention was given to the potential impacts on persons and families. The group engaged the family member by:

- co-creating the implementation plan

- involving them in a failure mode affects analysis, which highlighted the impact of the feeding tube supplies on transitions to home, school, and other care settings

- working with the family member to advocate for safe transitions within the provincial pediatric system, which led to the development of the Ontario Pediatric ENFit™ Group

To learn more about Holland Bloorview’s experience in partnering with families in a co-design process, watch their 38-minute webinar: The Power of Family Partnerships.