Adapt knowledge to local context

- Adapt knowledge to local context

- 1 What is this phase?

- 2 Why is this phase important?

- 3 Assessing the local context

- 4 Assessing your local context including the level of support and influence of others

- 5 Analysis of external partners

- 6 Case studies

- 7 Practice tips

- 8 Check your progress

- 9 Linking this phase to other framework components

- 10 More resources

Index

- 1. What is this phase?

- 2. Why is this phase important?

- 3. Assessing the local context

- 4. Assessing your local context including the level of support and influence of others

- 5. Analysis of external partners

- 6. Case studies

- 7. Practice tips

- 8. Check your progress

- 9. Linking this phase to other framework components

- 10. More resources

As change never occurs in isolation and is always impacted by the context (or setting), it is essential for change teams and others to examine their context and how these variables inform and shape the planning, achieving and sustaining of a practice change.

What is this phase?

- Once you have identified the problem and selected a practice change (for example, assessing older adults' risk of falls on admission) or intervention (for example, selecting and using a valid fall risk assessment tool, educating staff on using the tool or having the appropriate staffing levels to conduct a fall risk assessment), you are now ready to consider whether this practice change or intervention is suitable for your practice setting.

- Before you make a practice change or introduce any intervention, you must determine how well it fits within your context. This phase helps you consider the local context and the implications of introducing the practice change or intervention within that context (Harrison et al., 2013). It will also help you consider how to adapt knowledge such as evidence on best practices or interventions to your setting while maintaining the integrity of the practice or intervention.

- At this phase, others – individuals, groups, or institutions that are directly or indirectly influence or are influenced by change – are engaged at the planning level to make sure that the knowledge is:

- suitable to meet the needs of end-users who will be affected by the practice change

- compatible with the context

What is context?

Context is the setting or environment where the practice change or intervention is taking place and includes those people involved in the change. While there are multiple definitions, most scholars agree that context can be defined as “everything else that is not the intervention” (Nilsen and Bernhardsson, 2019). Contextual factors that influence the uptake of new knowledge can exist at the micro (individual), meso (organizational) and macro (system) levels (Rogers et al., 2020).

Identify any adaptations needed to the knowledge

When identifying any adaptations needed to the knowledge, here are some questions to keep in mind:

- How does your context differ from the one in which the knowledge was originally created and evaluated?

- How will you, your collaborators and end-users identify any adaptations needed so that the knowledge is appropriate to the local context while upholding the consistency of the evidence?

- How will you document the adaptations to the knowledge?

- What process will be put in place to update the knowledge, if necessary?

SOURCE: Health Canada, 2017.

Decide which components of the knowledge to adapt:

In most cases, it is possible to adapt knowledge to some degree, while still maintaining the integrity of the knowledge. The following points can help when planning and choosing which components of the knowledge can and can’t be adapted (Centre for Effective Services, 2021; Chambers et al., 2013; RNAO, 2012):

Define the intervention – Define and document the different components of the intervention, and distinguish between the components which are essential for the intervention to be effective (the core components) and those which can/should be adapted to the local context.

Identify the core components – the essential and indispensable elements which can’t be changed without undermining the intervention. You will need to work with the people who developed the intervention to identify the core components and deliver them with fidelity. Note that in some cases, it’s possible that all components may be core components.

Plan the adaptable components – These elements may be tailored to local settings. In the absence of this, the knowledge you are trying to get into routine practice could be a poor fit for the local setting, generating resistance from those involved and resulting in poor outcomes. You and your team will need to determine to what extent the knowledge needs to be adapted to your local context. This can be done in formal or informal ways, depending on the extent of adaptation (Graham et al., 2013; RNAO, 2012). Examples of approaches include: pilot testing recommendations, sharing plans with your collaborators and advisory teams, and hosting a workshop to review the evidence (Field et al., 2014).

Why is this phase important?

Knowledge or evidence developed in a controlled setting such as a randomized trial may be difficult to implement in your practice setting. You will need to consider the fit of the knowledge to the end users who will be using it. These end users might include providers, patients/persons and other collaborators in one or more settings. To convert the knowledge into routine practice, adjustments to the knowledge to tailor it to the needs and settings of your end users might be required.

Example: When introducing a new best practice guideline, you may find that not all recommendations are appropriate to the culture of your end users. Or, implementing the guideline may require materials, equipment, or resources that are not available. If so, you can adapt the guideline, being careful to keep it grounded in the evidence.

Remember: Contextual differences (for example, the number of resources your setting has or the types of equipment being used) could affect the appropriateness or feasibility of particular recommendations, even when those recommendations have been supported by a strong body of evidence.

Understanding your local context is critical for success

Understanding your local context improves engagement and support for the change

Assessing the local context

Now that you have identified the individuals, groups and organizations who will be participating in the change, you can engage them to assess the context in which the knowledge will be integrated. Assessing the local context can help you and the others engaged in the change understand more about how the knowledge can fit into your end-users’ setting. This is important so that you can optimize the knowledge uptake.

Knowledge created for one setting may not be suitable for or feasible within your local context. For example, you may notice differences in scopes of practice or regional legislation. Or, you may be concerned that best practices will be challenging to adopt due to a lack of skill, expertise, equipment or staffing in your organization (Harrison et al., 2010).

Note: some recommendations may not be culturally appropriate or acceptable to staff or persons/patients (Harrison et al., 2013; RNAO, 2012).

Context levels

Context can be viewed at three different levels (Nilsen et al., 2020):

|

Image

|

Micro level: Characteristics of the individual providers, persons/patients, or clients. |

|

Image

|

Meso level: Characteristics of the organization (culture, climate, infrastructure and support). |

|

Image

|

Macro level: Characteristics of political and economic forces beyond an organization (for example, legislation, funding, national guidelines, policies, or collaborations with other organizations). |

Context dimensions and their description

Context has been described and categorized by researchers in many different ways (Li et al., 2018; Nilsen and Bernhardsson, 2019; Squires et al., 2019a; Squires et al., 2019b) that span across the micro, meso and macro levels. The list below includes the 12 most commonly considered context dimensions to influence the implementation of a practice change or intervention (Nilsen and Bernhardsson, 2019).

Micro level - Individuals

The preferences, expectations, attitudes, knowledge, needs and resources of persons/clients or health professionals can influence implementation.

Meso level - Organizational culture and climate

Shared visions, norms, values, assumptions and expectations in an organization that can influence implementation (that is, organizational culture) and perceptions and attitudes concerning the observable aspects of culture (that is, climate).

Readiness for change

Support

Structures

Macro level - System-wide environment

External influences on implementation in health-care organizations, including policies, guidelines, research findings, evidence, regulation, legislation, mandates, directives, recommendations, political stability, public reporting, benchmarking and organizational networks.

Multiple (micro, meso, macro) levels

Social relations and support

Influences on implementation related to interpersonal processes, including communication, collaboration and learning in groups, teams and networks, visions, conformity, identity and norms in groups, and opinions of colleagues.

Financial resources

Funding, reimbursement, incentives, rewards, costs and other economic factors that can influence implementation.

Leadership

Influences on implementation related to formal and informal leaders, including managers, key individuals, change agents, opinion leaders, or champions.

Time availability

Time restrictions can influence implementation evaluation, assessment and various forms of mechanisms that can monitor and feedback results concerning the implementation.

Feedback

Evaluation, assessment and various ways that can monitor and feedback results about the implementation, can influence implementation.

Physical environment

Features of the physical environment that can influence implementation, such as equipment, facilities and supplies.

SOURCE: Nilsen and Bernhardsson, 2020

Interacting effects of contextual factors

Keep in mind that contextual factors are interrelated – they work synergistically to promote or hinder implementation efforts. For example, a lack of staff time and insufficient funding will likely affect the organization’s readiness for change. On the other hand, enthusiastic leaders and the presence of champions can help create a positive organizational culture and climate (Nilsen and Bernhardsson, 2019).

"Deadly combinations"

Different contextual factors that are unfavourable to your change initiative can work together to hinder or even halt implementation efforts (Johns, 2006; Li et al., 2018). For example, a culture that is not supportive of change, coupled with limited staffing or financial resources, will likely have a negative influence on outcomes.

It is important to assess your context and consider the various factors that could affect the success of your initiative. You can assess your context based on the 12 common context dimensions listed above, or refer to the validated tools for a more detailed assessment.

Establishing robust infrastructure

After assessing the local context, you might recognize the need for more financial resources, staffing, people with particular skills, or a reporting structure. Examples listed under “Additional resources” – for example, leadership or establishing a collaborative change team – can help you meet these needs and establish the infrastructure required for successful implementation and sustainability.

Example: A strong infrastructure is critical for the success of sustainable practice change. For example, the infrastructure requirements for RNAO Best Practice Spotlight Organizations® (BPSO®) include (Bajnok et al., 2018b, p. 149):

- a steering committee with key partners at different leadership levels in the organization

- a “BPSO sponsor” who champions the BPSO program within the senior leadership team

- a BPSO lead who devotes at least half of their work time to overseeing and mobilizing the initiative

- implementation teams and best practice guideline leads who are content experts on the topic and enable comprehensive implementation of best

- time and resources to develop champions to mentor, teach, role model and motivate their peers

- development of structures to support reporting and decision-making

Accelerate your success: The Social Movement Action Framework’s element ‘Change is scaled up, scaled out, or scaled deep’ can help you and your team begin to think about how your change can make a lasting impact within and (if applicable) beyond your local setting. Keeping in mind how your change can be expanded to another similar setting (scaled up), be modified to expand to a different setting (scaled out), or ensure that the norms and values of this change are deeply rooted in individuals who practice the change (scaled deep); may assist you with thinking of ways to sustain the change.

Assessing your local context including the level of support and influence of others

Once you have identified which components of your practice or intervention can and can’t be adapted to the local context, you are ready to identify the individuals, groups or organizations who can give you input on how to adapt the intervention to their local context. These persons play an essential role in any change process and need to be involved throughout the process. They can include end users, providers, persons/patients, or any individual who can indirectly or directly influence or be influenced by the knowledge you are trying to integrate into routine practice (Legare et al., 2009; RNAO, 2012).

They can support, oppose, or remain neutral about the knowledge in question and/or about the change initiative itself (RNAO, 2012).

Why are these persons important to your change?

These persons have in-depth knowledge and understanding of how a practice change can be successfully incorporated into their local context (Squires et al., 2021). To be effective in your change work, you will need to identify these persons and understand their goals, concerns and interests, and work to build their support and involvement in the change process (RNAO, 2012; Bowen and Graham, 2013).

Remember: As a change team, you will need to work collaboratively with others and maintain contact throughout the change process. This is critical for the sustainability of your change initiative (Bornbaum et al., 2015; Lennox et al., 2018). Use an analysis approach of these persons and organizations to help you do this.

Analysis of external partners

Stakeholder mapping

Gamestorming stakeholder analysis

How to engage the persons and organizations impacted by the change

Approaches that help to build relationships and engagement include:

- hosting in-person or virtual meetings

- visiting external organizations

- conducting one-to-one or group meetings

- keeping in regular contact by phone or email

SOURCES: Bornbaum et al., 2015; Lennox et al., 2018.

Case studies

Adaptar la guía de buenas prácticas Cuidados centrados en la persona y la familia al contexto local en Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre

Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre (SLMHC) es una institución de Cuidados de Larga Duración candidata a Centro Comprometido con la Excelencia en Cuidados® (BPSO®) de Sioux Lookout, una ciudad en el Noroeste de Ontario. SLMHC es un centro de servicios hospitalarios ambulatorios y de hospitalización que presta servicios a Sioux Lookout y 28 comunidades del norte. El área que cubre es remota, está aislada y comprende 385.000 kilómetros cuadrados, con una población del 85% de Primeras Naciones.

Como parte del proceso de candidatura, el equipo de cambio del SLMHC implantó la guía de buenas prácticas (GBP) sobre Cuidados centrados en la persona y la familia. Durante el proceso de implantación, el equipo de cambio del SLMHC trabajó para adaptar la GBP al contexto local en su organización, de forma que pudieran atender de la mejor manera posible a la población circundante, así como a otras comunidades remotas.

El contexto local del SLMHC planteaba retos únicos. Entre otros:

- La guía estándar sobre privacidad no siempre era aplicable a los miembros de las comunidades de las Primeras Naciones atendidos. Algunos miembros deseaban que se compartiera su información sanitaria con su jefe y su comunidad.

- Algunas personas tenían que viajar hasta 400 o 500 km para regresar a su domicilio tras el alta en SLMHC. Así, era esencial gestionar transiciones asistenciales adecuadas y asegurarse de que las personas que recibían el alta no perdieran sus efectos personales.

El equipo de cambio del SLMHC adaptó la GBP Cuidados centrados en la persona y la familia al contexto local:

Resumen del alta para el paciente de SLMHC. Compartido con autorización.

- situando los nombres en las puertas de las habitaciones del hospital de algunos individuos, de forma que los miembros de su comunidad pudieran pasar a visitarles

- creando un resumen del alta para el paciente que incluyera las siguientes opciones para indicar las preferencias de la persona en cuanto a compartir su información sanitaria:

- consiento en que mi información sanitaria se comparta con________

- no consiento en que se comparta mi información sanitaria con personas de mi comunidad (por ejemplo, agrupación o consejo)

- creando una detallada lista de verificación del personal dentro del resumen del alta orientado al paciente para garantizar transiciones asistenciales seguras (por ejemplo, enviando por fax el formulario completado a un orientador indígena para la transición, o incluyendo una relación de los efectos personales recogidos en la habitación)

- trabajando con un mediador indígena para la transición, cuyas funciones son, entre otras, realizar llamadas telefónicas de seguimiento con la persona, hacer rondas de pacientes y coordinar transiciones seguras.

Después de crear satisfactoriamente un resumen del alta orientado al paciente personalizado que respondiera a las necesidades de las personas atendidas, el SLMHC ha podido apoyar mejor los cuidados centrados en la persona y la familia dentro de la organización.

Compartido con autorización de Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre

Adapting BPG recommendations to a public health context – Insights from Toronto Public Health

Toronto Public Health – a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Canada – has implemented several RNAO best practice guidelines (BPGs), including Woman Abuse: Screening, Identification and Initial Response (2005) and Preventing and Addressing Abuse and Neglect of Older Adults (2014). Because some practice recommendations in these guidelines focus on the individual person or patient level, they didn’t always align with Toronto Public Health’s population health approach.

To adapt recommendations to the public health context, the change team completed a literature review to explore definitions and adapt strategies to align with the model of care delivery and health promotion philosophy.

Another approach that was taken by Toronto Public Health: piloting BPG recommendations within one small program team. The team would then evaluate the implementation until successful, consistent with the Plan-Do-Study-Act approach). Once successful, the intervention was scaled up within the organization to other programs and teams (Timmings et al., 2018).

Adapting BPG recommendations to a Chinese acute care context to reform care delivery– lessons learned from DongZhiMen Hospital

DongZhiMen Hospital – a BPSO in Beijing China – was motivated to reform care delivery through the use of RNAO BPGs. While best practice recommendations provided general guidance, DongZhimen Hospital identified the need to translate these statements into detailed instructions and parameters tailored to their specific hospital context.

To adapt statements to their context, they translated the guideline into Chinese. A multidisciplinary team then worked through the initial steps of the Knowledge-to-Action Framework. This involved:

- reviewing carefully the evidence to thoroughly understand the intent of the recommendations

- conducting a comprehensive gap analysis

- interviewing staff members and others to identify facilitators and barriers to the use of the BPG.

Using this information, the team was able to create specific, clinical nursing practice standards derived from the recommendations and relevant to their context (Hailing and Runxi, 2018).

Practice tips

- Build a collaborative change team that includes people with a variety of skills and perspectives.

- Respect the perspectives of end users, even if they are not in agreement with yours.

- Be mindful about how the knowledge can be adapted to the end users’ setting. Ask yourself, “Do the adjustments we are making jeopardize any part of the knowledge?”

- Determine what resources you might need to modify any part of your local setting for the new knowledge.

- Recruit champions as “bottom-up” leaders and build a strong network of champions who can support one another to mobilize change.

To adapt a change to your local context typically requires resources. Use the links below to support acquiring the resources you need.

Download the worksheet "Budget planning table".

Download the checklist "Business case development checklist".

Check your progress

- You have used a process or tool to assess your local context.

- You have identified aspects of the knowledge tool that may need adaptation for your context.

- You have identified factors that may aid or hinder successful implementation.

- You have found resources that may be useful in addressing contextual challenges.

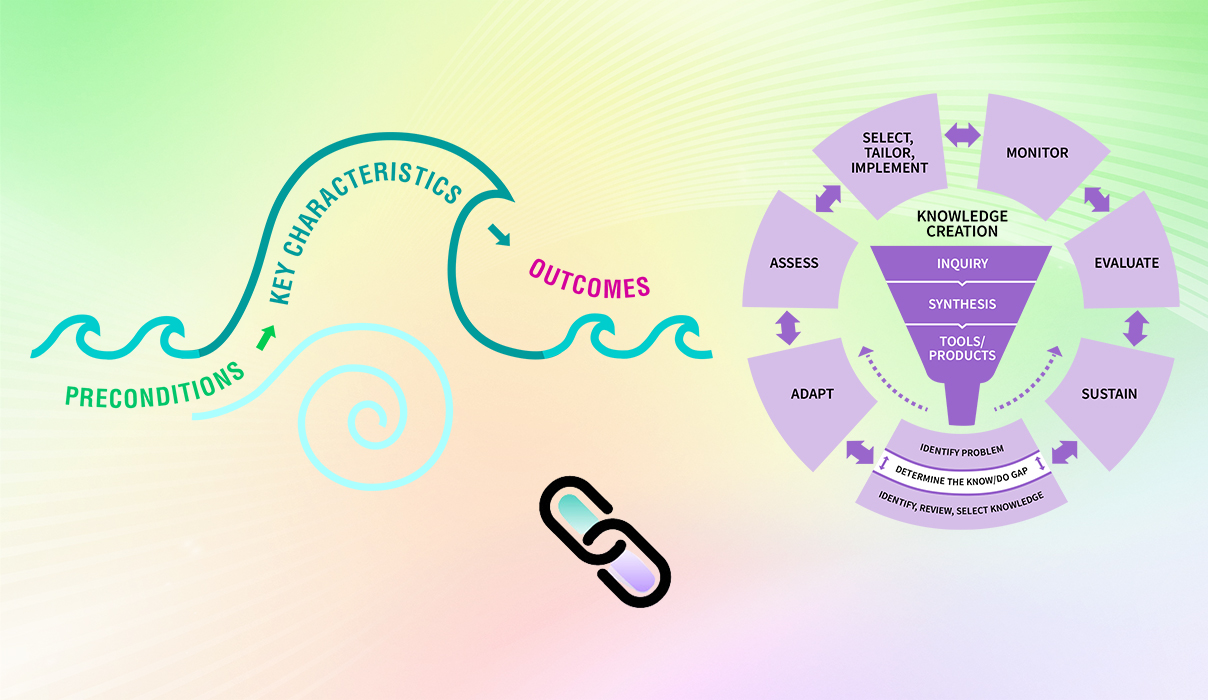

Linking this phase to the elements of the Social Movement Action Framework

You and your change team’s capacity in the “Adapt knowledge to local context” phase may be enhanced or accelerated by adding in some of the elements of the Social Movement Action Framework, as the two frameworks are complementary. In addition to the linking example described earlier in this section, there can be many other points of connection between the two frameworks. Below are two more examples for your consideration:

- Receptivity to change: As part of the assessment of the local context, the change team can also determine the level of support for the identified problem or shared concern by others, and their willingness to take action for it. When the shared concern is seen as credible and valued, it indicates a high level of commitment to the cause and a readiness to take action that enables the local context for change.

- Networks: When assessing the local context, partners and resources, it will be important to determine these three elements in the context of networks. Networks can help you determine which contexts and individuals, groups and organizations are accessible for you to implement your change.

For more discussion about the dynamic links between the elements of the SMA Framework to the KTA Framework, see the section "Two complementary frameworks".

Getting ready for the next phase: Once you have assessed the local context, and you and your change team have decided to go forward with the practice change, you are now ready to assess the barriers and facilitators in your practice setting. This upcoming phase can help you and your change team to identify the barriers you can address and facilitators you can leverage. Assessing the barriers and facilitators can help you maximize your chances of successfully implementing the practice change or intervention in your local setting.