Case studies

Social Movement Action Framework

Mobilizing communities for HIV prevention

Social movement strategies have been effectively applied to advance and advocate for HIV prevention. Read more in this case study.

Social movement strategies to engage and mobilize communities have been effective at reducing HIV transmission. Community-based interventions have made significant advancements in HIV prevention, including:

- decreasing discrimination against those who are HIV positive;

- raising the levels of HIV testing and counseling amongst young adults;

- improving access to program and service quality; and

- increasing the uptake of antiretroviral treatment to prevent transmission to non-infected partners.

Engaging and mobilizing communities – including members of stakeholder groups and civil society agencies – has been critical in taking collective action towards the goal of preventing HIV transmission. To be effective, communities were found to need the following three key components:

- empowerment through elements, such as leadership, resources, program management and the support of external partners

- development of having a collective or shared identity as a community

- capacity in health promotion, including the development of knowledge and skills, available resources, civic engagement, values for change and a learning culture

Applying grassroots advocacy for girls and women with disabilities and Deaf women

Using collective action, the Disabled Women's Network (DAWN) has advocated for the rights of girls and women with disabilities.

In 1985, 17 women with disabilities across Canada met in Ottawa to form what would become the Disabled Women’s Network (DAWN Canada), one of only a few similar networks globally. These women united in their commitment to creating a national cross-disability organization to advocate for the rights of all women with disabilities and Deaf women through a lens of feminist leadership.

DAWN Canada is a powerful example of an organization built by grassroots efforts and collective action. Its mission targets key areas of shared concern for women with disabilities including discrimination, poverty, unemployment and violence and the promotion of health equity and access to justice. To build support and public visibility, they applied grassroots actions and strategically partnered with other organizations who also advocated for the rights of women and persons with disabilities and the end of systemic marginalization, including labour unions. Researchers and academics joined the effort to promote a feminist disability lens as a standard of practice.

DAWN Canada remains an active and committed disability advocacy organization at all levels:

- at the micro level, they support women and girls with tools to build their self-determination and leadership

- at the community level, they improve programs to support the needs and rights of women and girls with disabilities and Deaf women

- at the macro level, they advocate for policy reform

The Alabama Comprehensive Cancer Control Coalition

A coalition of community partners who took action and created change for cancer prevention and promotion.

In Alabama, United States, a public health community coalition targeting breast and cervical cancer prevention engaged in grassroots advocacy to influence policy and legislation for smoke-free spaces (Wynn et al., 2011).

This coalition was made up of local stakeholders, including an interdisciplinary committee of government officials, faith-based organizations, academics, researchers and volunteers. Their collective efforts were effective in part because the people involved were receptive to change.

There was a strong impetus for change caused by these concurrent factors:

- data showing an unequal burden of cancers among Black Americans due in part to higher rates of tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure.

- recognition that the risk of cancers could be lowered by: implementing evidence-informed strategies; increasing public awareness and advocacy; and promoting healthy public policy.

- the coalition’s commitment to creating social change by improving the health and well-being of the community to achieve positive health outcomes.

- public support for the establishment of legislated smoke-free areas, evident from the results of local and national Gallup polls.

- an understanding of the powerful impact of social movement actions to create change.

This receptivity to change led the coalition to engage in social movement actions. They became empowered by learning strategies to lead change; they realized the power of their collective voices and mobilized actions. They felt their actions were timely and needed due to the data indicating rising cancer levels amongst Black Americans. They were committed to taking action to address and rectify health inequities.

Knowledge-to-Action Framework

Implementing effective interventions for drug and alcohol use using Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)

Evidence-based interventions to support the development of a screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for persons who use drugs and alcohol.

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is endorsed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration as an effective intervention for drug and alcohol use. SBIRT has been implemented in multiple health-care settings including acute care.

Implementation leaders were asked to identify barriers, facilitators, as well as implementation strategies that would be most helpful. From this review, implementation leaders perceived that providing ongoing consultation to clinicians for using SBIRT, distributing educational materials to clinicians, and conducting audits and providing feedback were the most helpful.

All implementation leaders voiced the value of available training resources, and peer support as they moved through the implementation process.

Implementation leaders felt more confident leading change in the future due to the knowledge and skills they developed during SBIRT implementation. They also learned the importance of leveraging support from other interprofessional team members, such as social workers and clinical educators.

Read more about it here. Learn more about SBIRT here. Or, review our best practice guideline, Engaging Clients Who Use Substances.

Adapting BPG recommendations to a public health context – Insights from Toronto Public Health

Toronto Public Health – a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) - has adapted several RNAO best practice guidelines (BPGs) to align with a population health approach.

Toronto Public Health – a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Canada – has implemented several RNAO best practice guidelines (BPGs), including Woman Abuse: Screening, Identification and Initial Response (2005) and Preventing and Addressing Abuse and Neglect of Older Adults (2014). Because some practice recommendations in these guidelines focus on the individual person or patient level, they didn’t always align with Toronto Public Health’s population health approach.

To adapt recommendations to the public health context, the change team completed a literature review to explore definitions and adapt strategies to align with the model of care delivery and health promotion philosophy.

Another approach that was taken by Toronto Public Health: piloting BPG recommendations within one small program team. The team would then evaluate the implementation until successful, consistent with the Plan-Do-Study-Act approach). Once successful, the intervention was scaled up within the organization to other programs and teams (Timmings et al., 2018).

Adapting BPG recommendations to a Chinese acute care context to reform care delivery– lessons learned from DongZhiMen Hospital

Care practices were revised using adapted evidence-based best practice guidelines in an acute care facility in Beijing, China.

DongZhiMen Hospital – a BPSO in Beijing China – was motivated to reform care delivery through the use of RNAO BPGs. While best practice recommendations provided general guidance, DongZhimen Hospital identified the need to translate these statements into detailed instructions and parameters tailored to their specific hospital context.

To adapt statements to their context, they translated the guideline into Chinese. A multidisciplinary team then worked through the initial steps of the Knowledge-to-Action Framework. This involved:

- reviewing carefully the evidence to thoroughly understand the intent of the recommendations

- conducting a comprehensive gap analysis

- interviewing staff members and others to identify facilitators and barriers to the use of the BPG.

Using this information, the team was able to create specific, clinical nursing practice standards derived from the recommendations and relevant to their context (Hailing and Runxi, 2018).

Engaging Persons with Lived Experiences

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital: Co-designing change through the active engagement of persons with lived experience

A case study from Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital focused on engaging persons with lived experience in a change process.

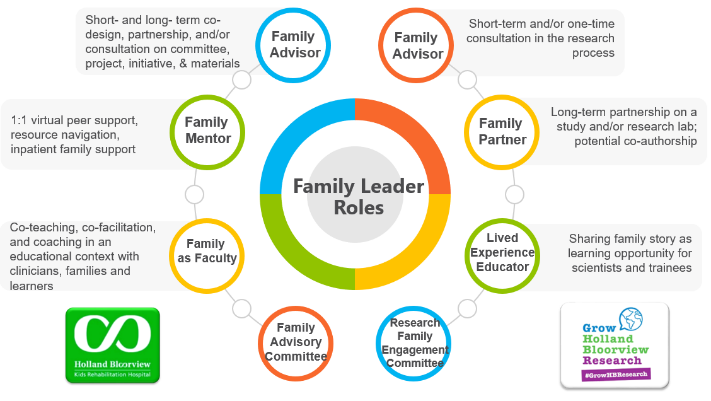

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital (hereafter referred to as Holland Bloorview) is a designated Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Holland Bloorview has an award-winning Family Leadership Program (FLP), through which family leaders partner with the organization and the Bloorview Research Institute to co-design, shape, and improve services, programs, and policies. Family leaders are families and caregivers who have received services at Holland Bloorview, and have lived experiences of paediatric disability. Family leaders’ roles include being a mentor to other families, an advisor to committees and working groups, and faculty who co-teach workshops to students and other families.

Family Leader Roles at Holland Bloorview. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

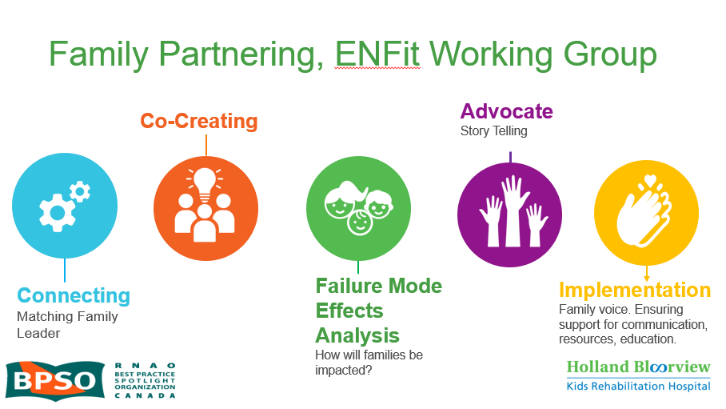

The ENFit™ Working Group is an example of a successful implementation co-design process within Holland Bloorview. The ENFit™ Working Group is an interprofessional team working on the adoption of a new type of connection on products used for enteral feeding [feeding directly through the stomach or intestine via a tube]. By introducing the ENFit™ system, a best practice safety standard, the working group plans to reduce the risk of disconnecting the feeding tube from other medical tubes, and thus decrease harm to children and youth who require enteral feeding.

Family Partnering with the EnFit Working Group. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

The working group invited a family member and leader whose son had received services at Holland Bloorview. This family member had significant lived experience with enteral feeding management, enteral medication administration, and other complexities associated with enteral products. During the meetings, great attention was given to the potential impacts on persons and families. The group engaged the family member by:

- co-creating the implementation plan

- involving them in a failure mode affects analysis, which highlighted the impact of the feeding tube supplies on transitions to home, school, and other care settings

- working with the family member to advocate for safe transitions within the provincial pediatric system, which led to the development of the Ontario Pediatric ENFit™ Group

To learn more about Holland Bloorview’s experience in partnering with families in a co-design process, watch their 38-minute webinar: The Power of Family Partnerships.