Case studies

Social Movement Action Framework

Scaling up, scaling out and scaling deep a fall prevention initiative

A joint fall prevention program by RNAO and the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI) that was scaled up, scaled out and scaled deep.

RNAO’s Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) program itself was scaled up, scaled out and scaled deep – on the national level – when RNAO and the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI) entered into a formal partnership on a pan-Canadian falls prevention initiative campaign in 2007, with a focus on long-term care (LTC) (McConnell et al., 2018).

This collaboration involved the implementation of best practices, capacity building at the micro and meso levels with individuals and organizations, and engagement with national partners. The work was informed by the first and second editions of RNAO’s best practice guideline (BPG) Prevention of Falls and Fall Injuries in the Older Adult and CPSI’s program Safer Healthcare Now! on falls prevention as a critical patient safety issue Reducing Falls and Injuries from Falls.

The National Collaborative on Falls Prevention in Long-Term Care, launched in 2008–2009, included staff from 32 LTC homes and an interprofessional expert panel. The goals of the collaborative:

- to reduce the rate of falls in older adults by educating and training staff and patients about fall prevention

- develop a forum for improvement teams

- participate in a methodology on quality improvement initiatives using the Model for Improvement (Langley et al., 2009).

The collaboration was highly successful – process indicators showed decreased rates of falls in the LTC homes following implementation. However, it was determined that more time and support would be needed to scale the fall prevention initiative out and deep to in order to embed and sustain the practice changes.

In 2010–2011, the collaborative expanded to a national campaign where the program was delivered virtually to more than 45 organizations from diverse health sectors using web-based technology. This enabled greater access to the program with impressive outcomes, and showed that technology could be used as a tool to scale the program up and out.

This was followed up by creation and delivery of a fall prevention learning series in 2011–2012 to strengthen the uptake and sustainability of best practices. The training integrated implementation science, change theory and quality improvement methodology. As with the other collaboration components, the outcomes of the learning series demonstrated improvements in practice changes and reductions in falls causing injury, and organizational policies to support and sustain the change. The continued use of evaluation to determine outcomes and impact as part of quality improvement and using ongoing audit and feedback demonstrated a change that was scaled deep.

The collaboration helped embed principles of social action movement by its focus on a credible and important shared concern – preventing falls – where urgent change was needed. Momentum was used to support the continued engagement of fall prevention champions across sectors. Networks were used to share resources and expand collaborations across communities.

Building capacity in change agents for health innovation and transformation

United Kingdom junior doctors increased their capacity as change agents after mobilizing and implementing the WHO surgical checklist.

Although positioned as the “future leaders of health-care transformation and innovation,” junior doctors (or interns) in the United Kingdom actually receive very little training in leadership competencies at medical schools to prepare for this role (Carson-Steven et al., 2013). Instead, they learn in clinical environments that are frequently unreceptive to change and innovation informed by best practices.

To overcome these barriers and emerge as leaders, a group of junior doctors chose to independently learn how to innovate and champion evidence-based practice by applying social movement approaches including mobilizing for change. By participating in programs, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Open Schools,” they built capacity in social movement thinking and actions and used their knowledge, skills, networks and experiential learning to drive change in their clinical practice.

The junior doctors applied social movement actions when they led a change initiative to implement the World Health Organization’s guidelines on the use of surgical safety checklists for patient safety. They co-created a supportive learning community to learn together and from one another and to overcome obstacles and resistance. As emerging leaders, they engaged in collective action, including organizing a “teach-in” to raise awareness about the urgent need for change and the implementation of best practices in surgical care as determined through evidence. And, each doctor committed to recruiting colleagues to strengthen the social movement and build momentum and a critical mass.

For more details, see The social movement drive: a role for junior doctors in healthcare reform - PubMed (nih.gov).

Championing BPG implementation at Clinica las Condes

at Clínica las Condes (CLC), a Latin American Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Santiago, Chile, BP Champions are committed volunteers consisting mostly of nurses and other health professionals. Their leadership is evident in the multiple activities . Learn more in this case study.

The Best Practice Guideline (BPG) Program has supported the leadership and influence of thousands of Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) Best Practice (BP) Champions as change agents engaged in the implementation of evidence-based practice changes.

For example, at Clínica las Condes (CLC), a Latin American Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Santiago, Chile, BP Champions are committed volunteers consisting mostly of nurses and other health professionals. Their leadership is evident in the multiple activities they lead, including:

- reviewing guidelines and organizational policies

- motivating colleagues

- presenting guideline recommendations at clinical services meetings twice a year

- ensuring adherence to practice changes in their clinical units

(Serna Restrepo et al., 2018)

Knowledge-to-Action Framework

Conducting gap analyses to successfully implement new clinical practices at Tilbury Manor

Tilbury Manor, a long-term care home, chose to focus on provincially-mandated “required programs” when seeking to improve resident care using a gap analysis.

Tilbury Manor, a 75-resident long-term care home in Tilbury chose to focus on provincially-mandated “required programs” (fall prevention, skin and wound care, continence care, bowel management and pain management) when seeking to improve resident care.

They conducted a gap analysis to compare their current practices with the best practices outlined in related RNAO best practice guidelines. Their analysis included an assessment of clinical practices, policies and documentation systems. The results of the gap analysis helped them create specific action plans.

Tilbury Manor then formed project teams led by nurses and supported by a team of champions. These teams proceeded to educate staff, implement new clinical practices, conduct care reviews and conduct audits.

Multiple positive outcomes were reported as a result of implementing these best practices including reductions in reports of pain, less use of restraints, and less falls, pressure ulcers and urinary tract infections.

Evaluating the impact of implementing the Person- and Family-Centred Care Best Practice Guideline at Spectrum Health Care

Spectrum Health Care, a Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) and home health organization, evaluated care outcomes after implementing the Person- and Family-Centred best practice guideline (BPG).

Spectrum Health Care (Spectrum), an RNAO Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®), is a home health organization with more than 200 nursing staff across three locations in the province of Ontario, Canada.

Spectrum chose to implement the 2015 Person- and Family-Centred Care (PFCC) Best Practice Guideline (BPG) to enhance person- and family-centred care and to reduce complaints regarding care. Members of the senior leadership team at Spectrum Health Care led implementation together with Spectrum’s Patient and Family Advisory Council.

To support the practice change, Spectrum used the following implementation interventions:

- Conducting a gap analysis to determine the knowledge/practice gap;

- Holding education sessions for staff on person- and family-centred care best practices;

- Revising their care processes to include review of care plans with the person and/or members of their family

- Surveying staff members on their attitudes about person- and family-centred care via surveys

- Developing staff education on communication strategies to support the assessment of a person’s care needs and care plans.

After implementing these interventions, Spectrum assessed the number of complaints received from persons receiving care per 1,000 care visits and compared that to their baseline.

They found a decrease of 42 per cent of complaints from persons received over an 18-month time period at one of the sites that was implementing the PFCC BPG at Spectrum Health Care.

At another site, an 80 per cent reduction in complaints was found following the staff education intervention.

Data analyses overall indicated that the implementation of the PFCC BPG was highly successful in reducing persons' complaints regarding care.

Read more about Spectrum Health care’s results of implementing the PFCC BPG here: Slide 2 (rnao.ca)

Leveraging innovative quality monitoring - Humber River Hospital

Humber River Hospital is an acute care facility that has used continuous monitoring to determine the impact of BPG implementation and staff performance.

A major acute-care hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Humber River Hospital (now Humber River Health) has used continuous monitoring to determine the impact of their BPG implementation and staff performance.

These tiles, displayed on large screen monitors in a Command Centre (pictured above), are integrated into the daily delivery of care to support physicians, nurses, and other clinical staff. Each row within the tile represents a patient, followed by where they are located. By clicking on a patient, staff can see more information regarding the clinical criteria that put them on the tile.

With every patient, there is an expected time in which the issue should be resolved based on a service level set by the hospital. If the system detects that the process is taking longer than expected, the icon will escalate to amber and then to red, indicating a higher level of alert.

Tiles also include several quality monitoring indicators based on RNAO's best practice guidelines (BPG) related to fall risk intervention, wound and skin management, pain management and delirium management. By centralizing data in the Command Centre, the monitoring indicators empower clinicians so that they can intervene in a timely manner to ensure that best practices are followed.

Read more about this innovative quality monitoring approach here: https://www.hrh.ca/2020/08/04/cc-risk-of-harm/

Engaging Persons with Lived Experiences

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital: Co-designing change through the active engagement of persons with lived experience

A case study from Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital focused on engaging persons with lived experience in a change process.

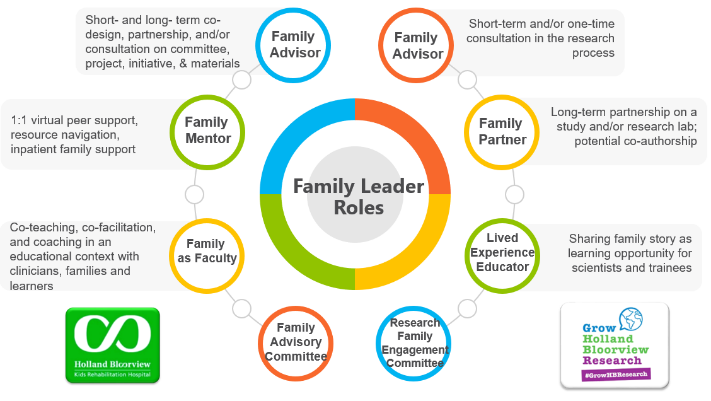

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital (hereafter referred to as Holland Bloorview) is a designated Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Holland Bloorview has an award-winning Family Leadership Program (FLP), through which family leaders partner with the organization and the Bloorview Research Institute to co-design, shape, and improve services, programs, and policies. Family leaders are families and caregivers who have received services at Holland Bloorview, and have lived experiences of paediatric disability. Family leaders’ roles include being a mentor to other families, an advisor to committees and working groups, and faculty who co-teach workshops to students and other families.

Family Leader Roles at Holland Bloorview. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

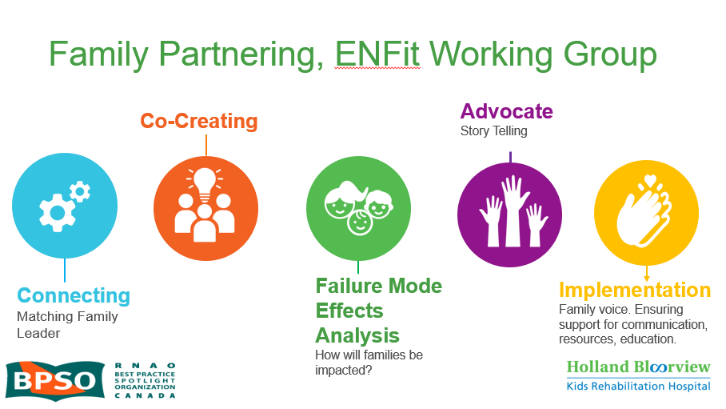

The ENFit™ Working Group is an example of a successful implementation co-design process within Holland Bloorview. The ENFit™ Working Group is an interprofessional team working on the adoption of a new type of connection on products used for enteral feeding [feeding directly through the stomach or intestine via a tube]. By introducing the ENFit™ system, a best practice safety standard, the working group plans to reduce the risk of disconnecting the feeding tube from other medical tubes, and thus decrease harm to children and youth who require enteral feeding.

Family Partnering with the EnFit Working Group. Photo provided with permission by Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

The working group invited a family member and leader whose son had received services at Holland Bloorview. This family member had significant lived experience with enteral feeding management, enteral medication administration, and other complexities associated with enteral products. During the meetings, great attention was given to the potential impacts on persons and families. The group engaged the family member by:

- co-creating the implementation plan

- involving them in a failure mode affects analysis, which highlighted the impact of the feeding tube supplies on transitions to home, school, and other care settings

- working with the family member to advocate for safe transitions within the provincial pediatric system, which led to the development of the Ontario Pediatric ENFit™ Group

To learn more about Holland Bloorview’s experience in partnering with families in a co-design process, watch their 38-minute webinar: The Power of Family Partnerships.